In the Audubon Story series, we will delve deeper into John James Audubon’s history to learn more about the people, places, and events that shaped his life’s course.

After viewing the original double-elephant folio prints from The Birds of America in our museum galleries, visitors sometimes ask us, “where is Audubon’s signature?” We’re accustomed today to seeing an artist’s signature and number on prints sold in limited editions. It is reassuring to us to see the artist’s distinctive way of writing their name and the presence of a signature serves as a visual “guarantee” that the print is authentic. Our answer to the question is that John James Audubon did not sign and number his prints. As Bill Steiner writes in Audubon Art Prints: A Collector’s Guide to Every Edition (2003):

“There are at least three reasons why the very thought would never have occurred to him. First, there was no precedent, because the practice of signing and numbering did not really begin until the early twentieth century. Second, he made his prints to go into books, not to be sold as collector’s items. Third, he and Havell probably did not foresee the market for his loose prints that exists today.”

Bill Steiner, Audubon Art Prints: A Collector’s Guide to Every Edition (2003), page 47.

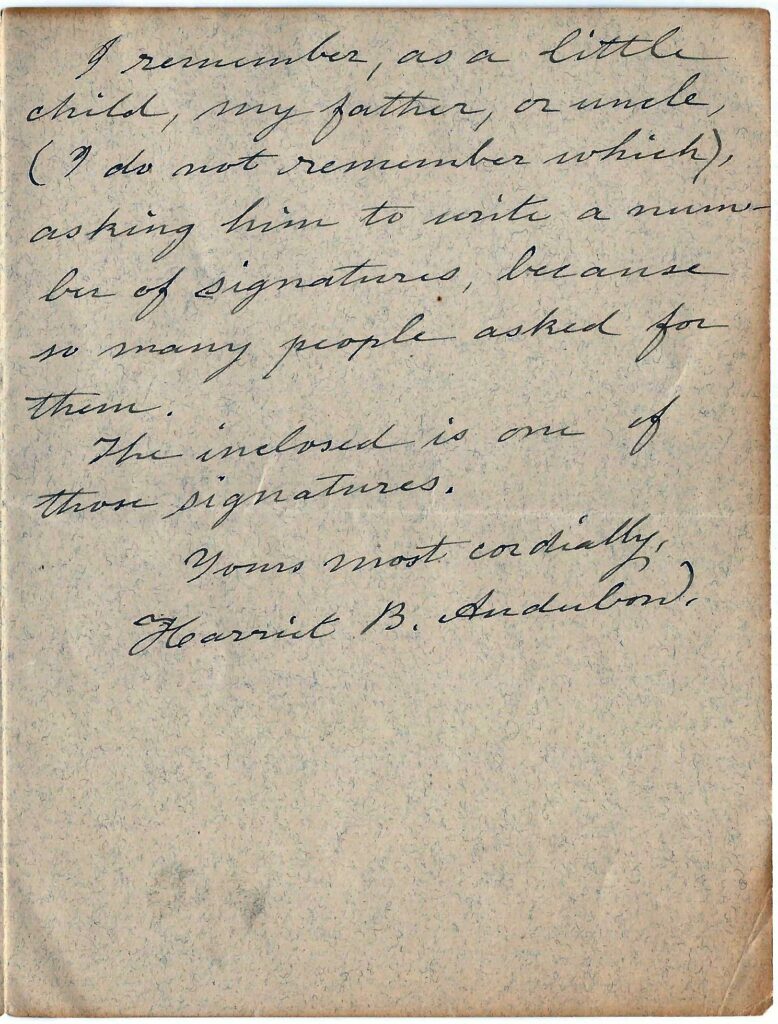

Are there any examples of John James Audubon’s signature out there? Yes. As Audubon’s prestige and celebrity continued to rise in his later years and after his death, copies of his signature became a coveted collectible item. There is evidence from archival materials in our museum collection that Audubon and his sons recognized the desirability of his signature and took action to supply the demand.

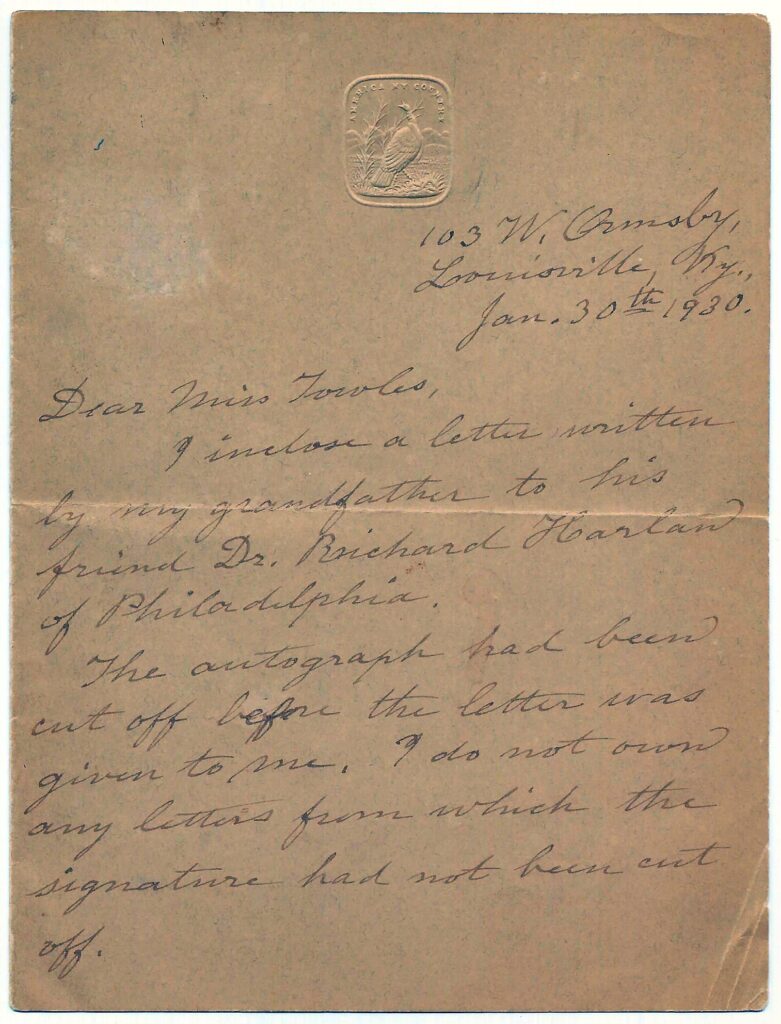

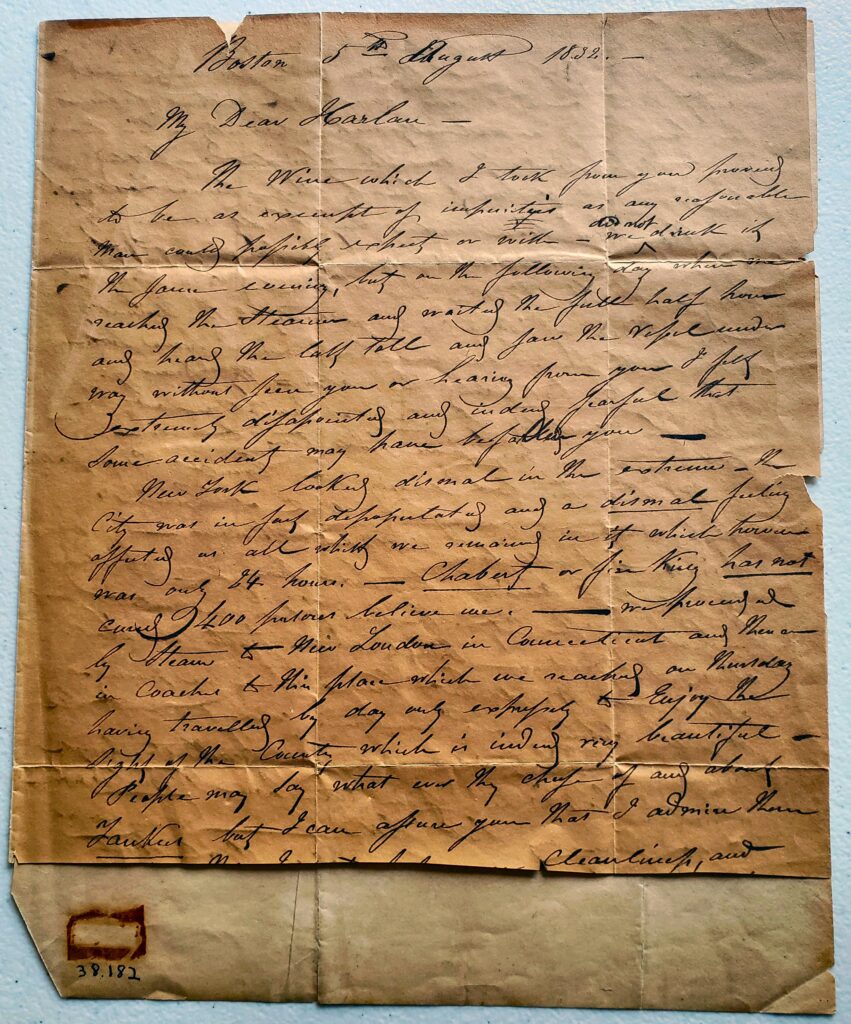

In January 1930, his granddaughter, Harriet Bachman Audubon, wrote a short note to Susan Starling Towles in Henderson, Kentucky. Enclosed was a letter written by her grandfather to Dr. Richard Harlan as well as a scrap of paper with Audubon’s signature that had been cut from another letter. In her note to Susan, Harriet apologized for the absence of Audubon’s signature on the letter to Dr. Harlan. She explained:

“The autograph had been cut off before the letter was given to me. I do not own any letter from which the signature had not been cut off. I remember, as a little child, my father, or uncle, (I do not remember which) asking him to write a number of signatures, because so many people asked for them.”

Letter from Harriet B. Audubon to Susan Starling Towles, January 30, 1930

Susan Starling Towles Collection, 1942.12

John James Audubon State Park Museum

Harriet Audubon Collection, 1938.182

John James Audubon State Park Museum

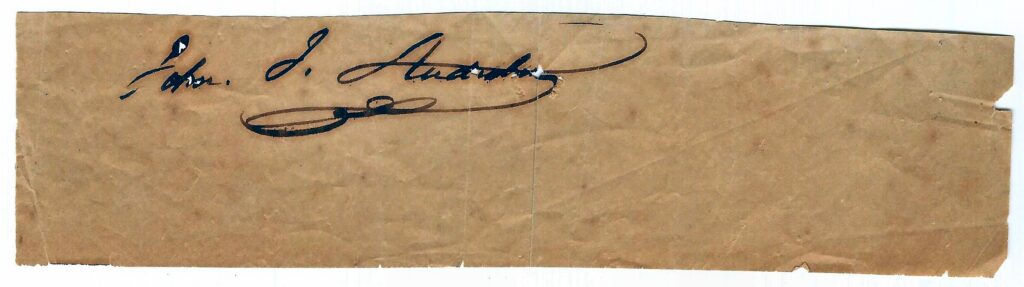

Autograph of John James Audubon, circa 1830

Found in Collection, 9999.0.38

John James Audubon State Park Museum

At the time she received Harriet Audubon’s letter in 1930, Susan Starling Towles was just three months away from making a statement before a joint hearing of the U.S. Congress in support of funding to build a museum in memory of John James Audubon in Henderson. Susan was entranced by Audubon’s art and his life story, and for years she had been collecting artwork, objects, and documents related to Audubon and his family. She reached out to Audubon’s descendants hoping to secure pieces of his material legacy for the future museum. Like other collectors, Susan wanted to feel a sense of connection to a person that she deeply admired.

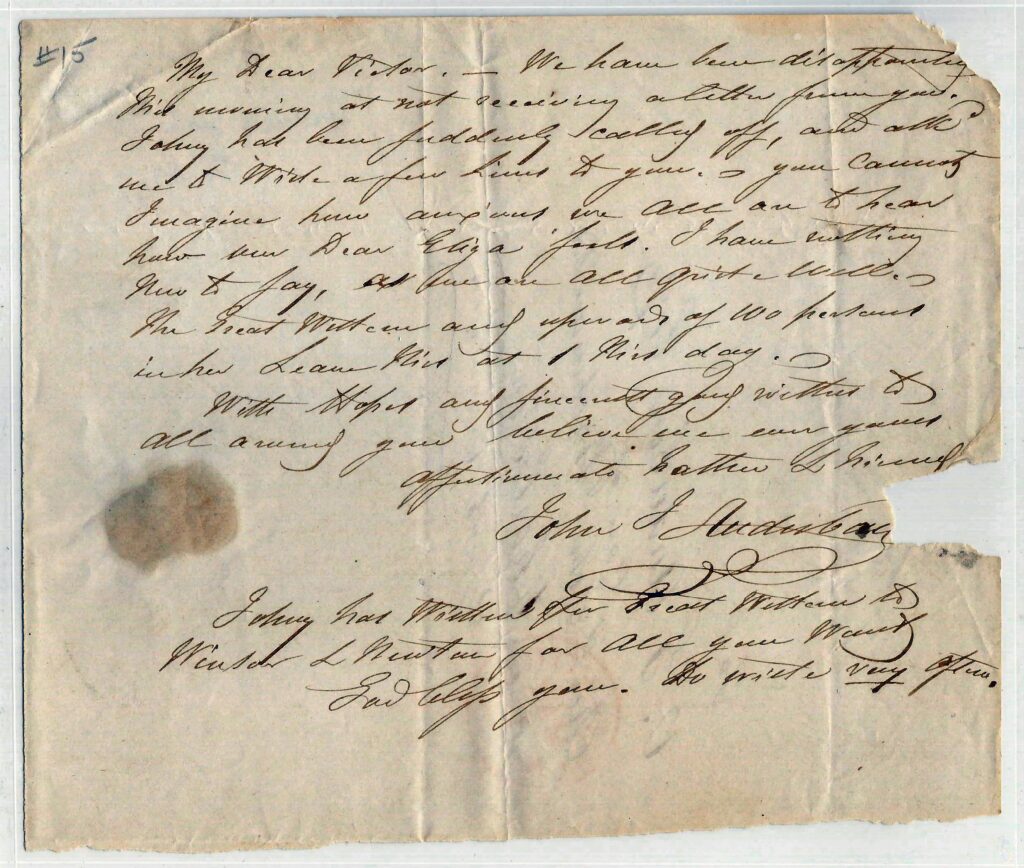

Thanks to Susan, Audubon’s descendants, and other generous donors to our museum over the past 82 years, we have several letters in our collection that still contain Audubon’s signature. One is a short handwritten letter that was sent by Audubon to his oldest son, Victor Gifford, around 1841 (image below). You can see that the signature on this letter is similar to the signature on the scrap of paper shown above. For both signatures, Audubon’s handwriting is slanted to the right, the middle letter J rises slightly above the line followed by the rest of his name, and is finished with a decorative twist.

L.S. Tyler Collection, 1938.360

John James Audubon State Park Museum

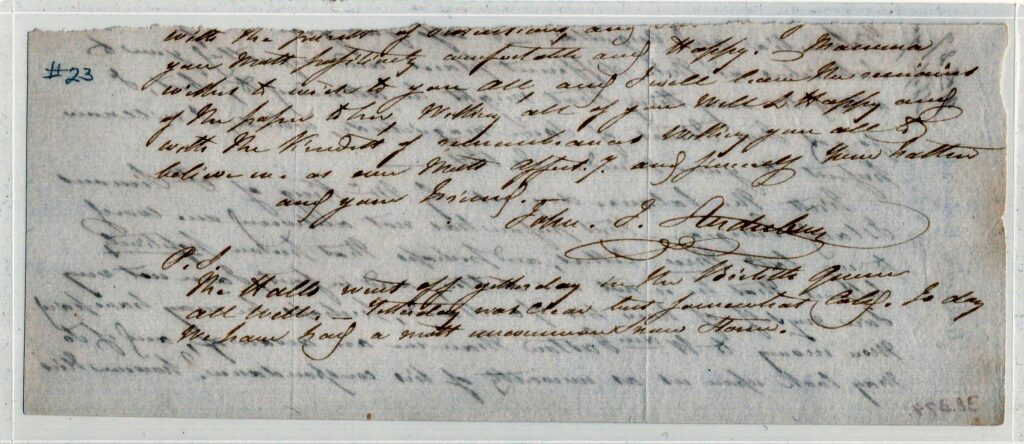

In this second fragment of a letter, written and signed by Audubon around 1835, you can see that his signature follows the same form as the other two signatures. Audubon’s written name in his hand is very easy to recognize once you know its characteristics.

L.S. Tyler Collection, 1938.374

John James Audubon State Park Museum

Do you collect signatures? Have you ever thought about why people want the autographs of historical figures? What do you think about the practice of cutting signatures from letters? I would love to know your thoughts.

This post was written by Heidi Taylor-Caudill, museum curator at John James Audubon State Park. Questions? Contact Heidi at 502-782-9716 or [email protected].

SOURCES:

Steiner, Bill. Audubon Art Prints: A Collector’s Guide to Every Edition. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, 2003.