In our Audubon’s Story series, museum curator Heidi Taylor-Caudill delves deeper into the histories of the people, places, and events that shaped John James Audubon’s life.

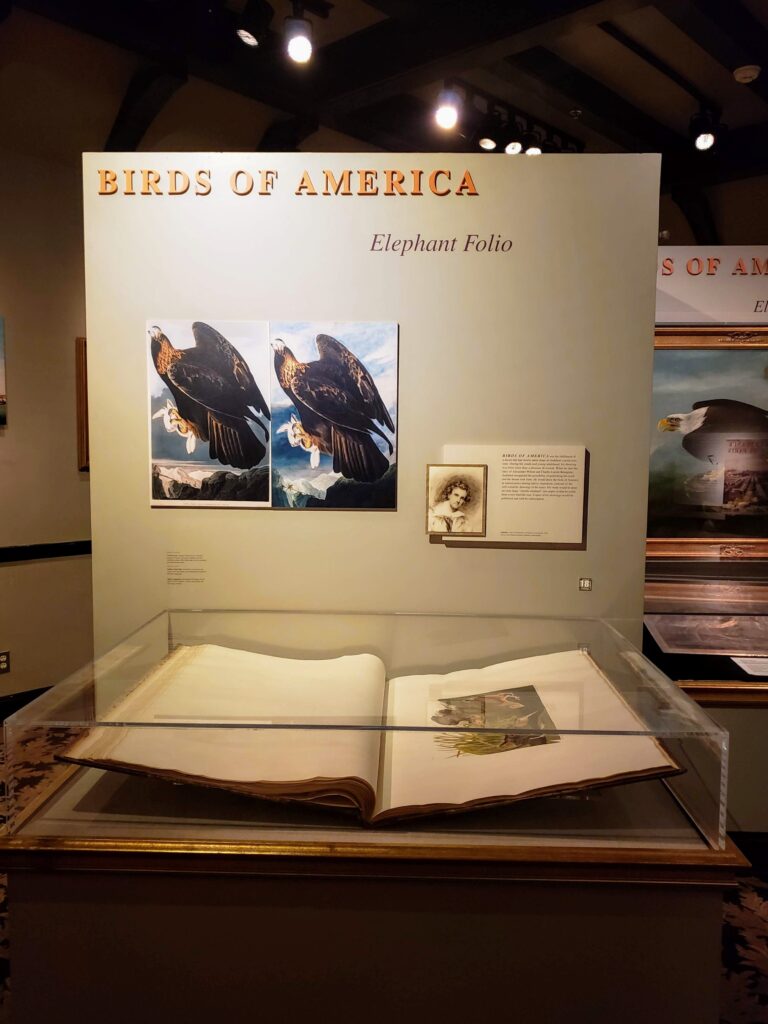

The Audubon Museum in Henderson, Kentucky, contains many treasures of Auduboniana (objects related to the life and work of John James Audubon), including a rare, intact, complete set of the Double Elephant Folio of The Birds of America in Gallery C. In this room, visitors can view an open volume of the Double Elephant Folio, two original copper engraving plates from The Birds of America, an original oil painting by Audubon of an American bald eagle, another Audubon oil painting of two black vultures, several beautiful Havell prints, and more. In fact, there is so much to see that it’s easy to pass by one of the smallest items in the museum’s collection without noticing it: a wax seal fob measuring no more than one inch wide. Today I’d like to share with you the story behind this object and why it was so treasured by John James Audubon.

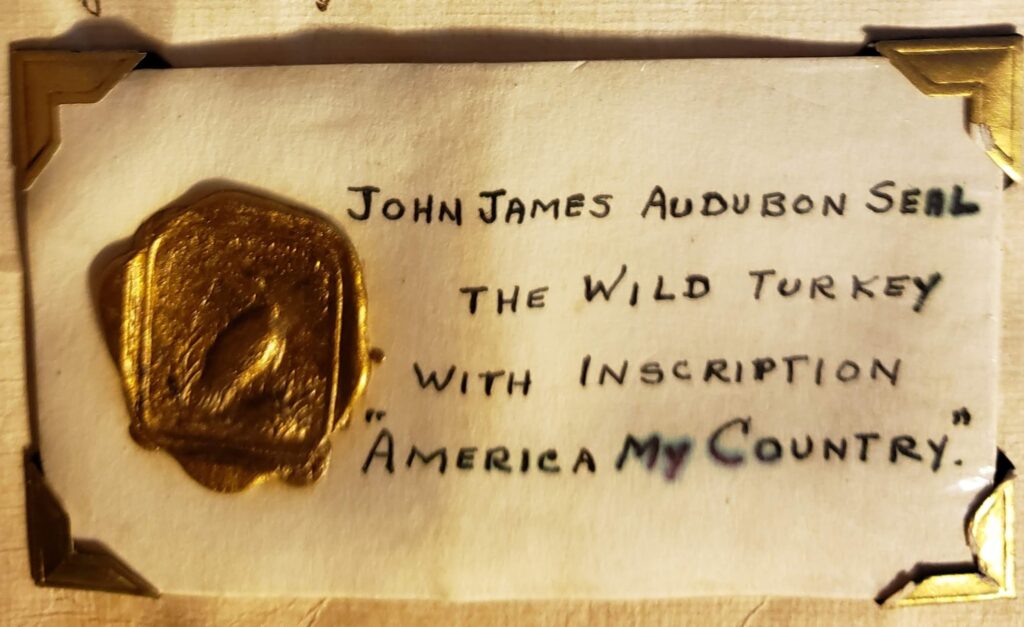

The wax seal fob features ornate gold details and a rectangular, red carnelian stone engraved with a miniature image of Audubon’s wild turkey. A motto, “America, My Country,” is engraved in a halo above the turkey.

Wax Seal Fob, 1826

L.S. Tyler Collection, JJA.1938.1199

John James Audubon State Park Museum

To understand Audubon’s joy, astonishment, and pride in receiving this wax seal fob as a present from a friend in 1826, we should first take a look at his life starting fourteen years earlier. In 1812, Audubon and his family were living in the small river town of Henderson, Kentucky. He and his brother-in-law, Tom Bakewell, had made plans for a new business partnership as consignment agents for a trading company. While Tom went to New Orleans, Louisiana, to start the venture, Audubon, his wife Lucy, and their young son Victor Gifford journeyed to Pennsylvania to visit her family. Audubon and Lucy dreamed of a happy, comfortable future in New Orleans, but their hopes were dashed by the outbreak of war between the United States and England in June of 1812.

Before returning home to Henderson, Audubon rode to Philadelphia to renounce his French citizenship and take an oath of allegiance to the United States.

“On July 3 [1812], Audubon made a special trip to the U.S. District Court in Philadelphia to swear his allegiance to the United States of America and become a true and legal citizen of the Republic…from that day on, he was a fervent, devoted American.”

Shirley Streshinsky, Audubon: Life and Art in the American Wilderness (1993), page 76

Over the next seven years in Henderson, Audubon attempted to provide financial security for his wife and children through various business ventures. He eventually went bankrupt during a nationwide economic depression in 1819 and had to sell everything the family owned. Audubon was even briefly jailed for their debts. It was one of the lowest points of his life.

As Audubon and Lucy struggled to get back on their feet in the early 1820s, he endured heavy criticism from family members, friends, neighbors, and acquaintances. Some blamed Audubon’s financial collapse on his consuming interest in birds and his passion for drawing them, saying that he had been selfish and too obsessed with pursuing his own amusements at the expense of his business. Weighing a choice between trying to restart his career as a businessman or taking a chance on earning money for his family through his artistic talent, he chose art.

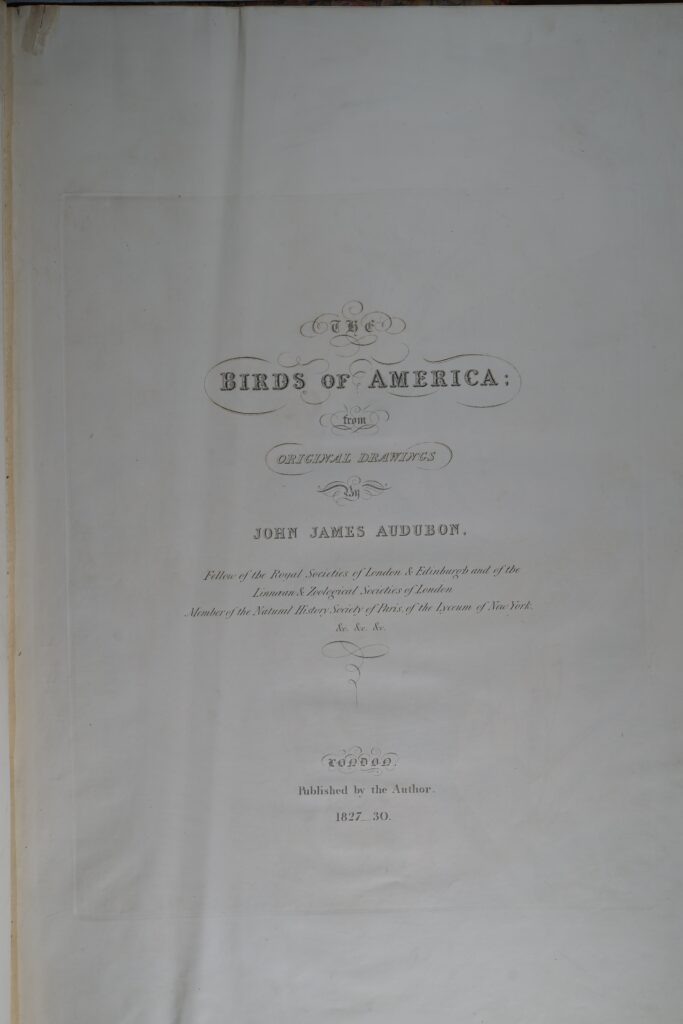

Audubon envisioned a project in which he would draw every bird species in North America and publish these illustrations as books of life-size, colored engravings. He attempted to find an engraver in the United States willing to work with him and gather support from the American scientific community, but he failed on both counts. Undaunted, Audubon and Lucy saved up enough money to send him to England in 1826 to seek a publisher. There, Audubon finally found success. He was able to hire two talented engravers, William H. Lizars and Robert Havell, Jr., to print his drawings. To finance the publication, he sold subscriptions to wealthy individuals. It took 13 years (1826-1839) to complete the project, The Birds of America, which now stands as one of the greatest works of natural history, illustration, and book printing.

John James Audubon State Park Museum Collection, JJA.1971.1

When Audubon arrived in Liverpool, England in the summer of 1826, he had no idea whether The Birds of America would turn out to be his life’s achievement or just another crushing failure. What was his motivation in pursuing this ambitious project? What drove him to leave his beloved wife and sons behind and travel thousands of miles to try to accomplish what many people would call a pipe dream? Bill Steiner, an expert on Audubon prints, offers this explanation:

“While it is certainly true that Audubon wanted the financial security a successful publication would bring, money was not his primary motivator. More than anything he wanted things to be the way they had been — when his family respected him, when studying and painting birds was entertainment. In his correspondence he reveals the ultimate goal of his work as paving the way to a life, with Lucy and his sons, filled with peace and harmony.”

Bill Steiner, Audubon Art Prints: A Collector’s Guide to Every Edition (2003), Foreword, page xiv

With so much at stake, Audubon was determined to make The Birds of America happen. To do this he would need to remain focused on his goals, project confidence in his artistic talent and scientific knowledge, and call on every ounce of his charisma to persuade people to support the project.

As Audubon set about introducing himself to potential subscribers to The Birds of America, he met Richard Rathbone, whose family members were prominent merchants, shipowners, politicians, patrons of the arts, and philanthropists in Liverpool. The Rathbone family soon took Audubon under their wing, arranging for him to meet influential people in Liverpool and inviting him to visit their country home, Green Bank. Audubon became particularly close to the family matriarch, Mrs. William Rathbone IV (Hannah Mary Rathbone), whom he affectionately called the “Queen Bee.” She would play a central role in the story of Audubon’s seal.

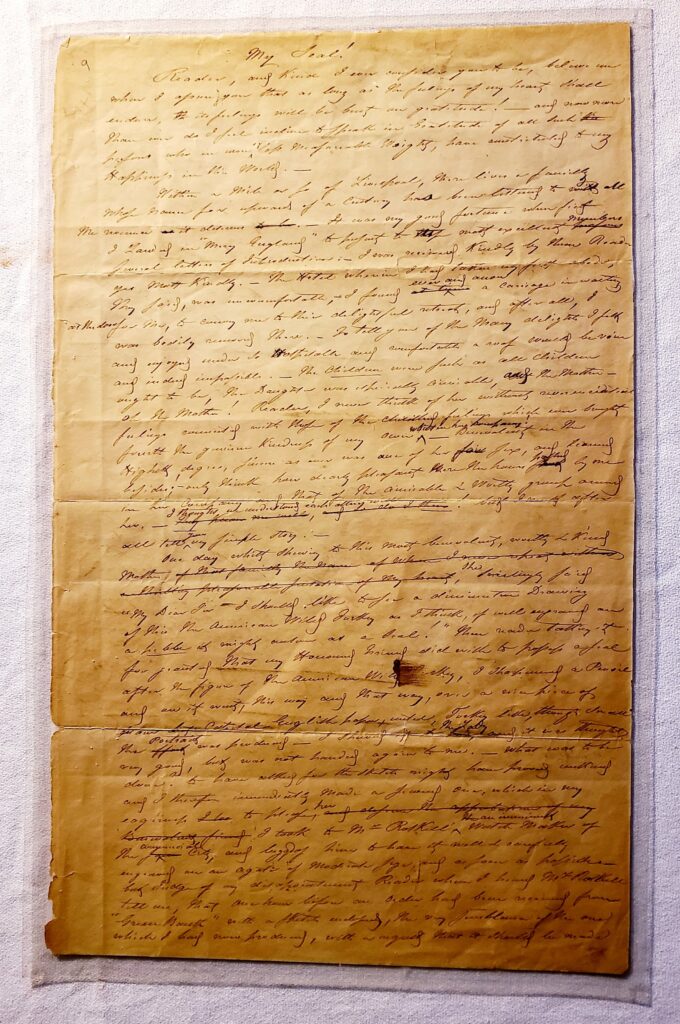

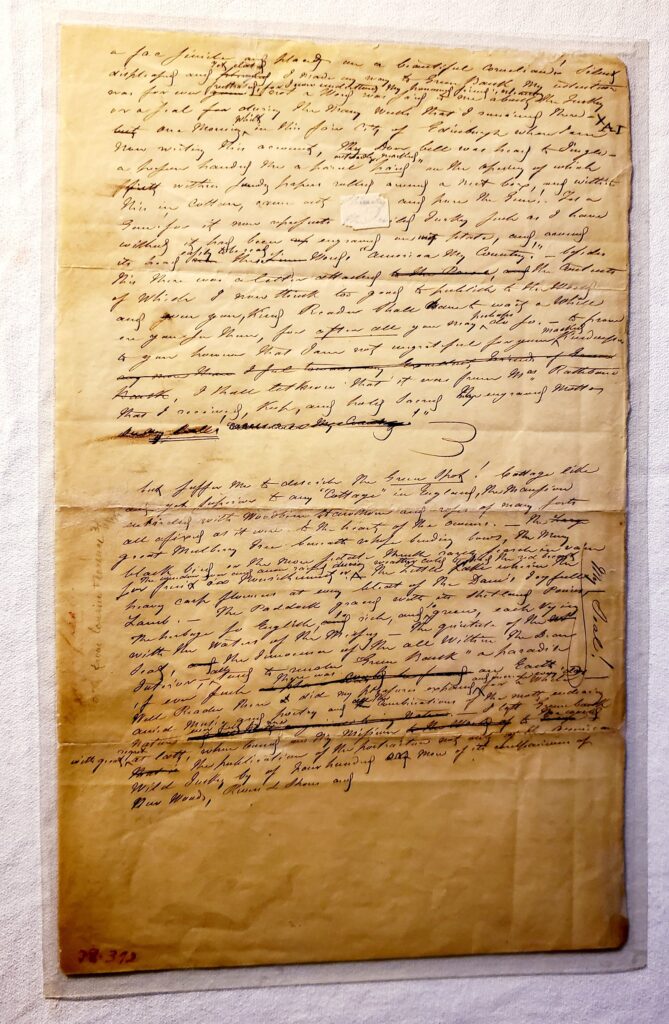

On October 2, 1826, Audubon wrote in his journal that Mrs. Rathbone asked him for a small sketch of his portrait of the American wild turkey, which she admired. He spent around 20 minutes drawing a thumbnail-sized version of the turkey (Herrick, 355). Audubon later described the incident in his undated manuscript, “My Seal!,” housed in the Audubon Museum collection. He writes that Mrs. Rathbone had mentioned to him that if well-engraved, his illustration of the wild turkey could serve as an excellent seal. Thinking that she meant to have a seal with the image for her own use, he set about recreating the portrait in miniature.

“I sharpened a pencil and as it went, this way and that way, over a nice piece of small but Capital English paper, until, Turkey like, though small the portrait was produced __ I showed it to the Lady and it was thought very good, but was not handed again to me.”

John James Audubon, “My Seal!,” page 1

Audubon wanted to demonstrate his gratitude to Mrs. Rathbone for her generosity and support. He impulsively decided to make a second sketch and take it to a watchmaker in Liverpool to be engraved into a seal for her. Before Audubon could place his order, however, he learned that the watchmaker had already received an order from “Green Bank” with the sketch of the turkey enclosed and instructions to cut it on a carnelian stone. Audubon returned to Green Bank disappointed that he could not make the gift to his friend and benefactor. He writes that “not a word was said to me about the jewelry or a seal during the many weeks that I remained there” (Audubon, 1).

John James Audubon State Park Museum Collection, JJA.1938.392

One morning in early November 1826, Audubon heard his door bell jingle and opened the door to meet a messenger holding a package. Unwrapping it, Audubon found a little box filled with cotton. He pulled out the contents and was shocked to see enclosed a gold seal fob with a beautiful engraving on an orange-red stone of his wild turkey and, haloed around its head, the words, “America My Country.” Included with the box was a kind letter from Mrs. Rathbone (Audubon, 1).

Audubon’s happiness in receiving this unexpected gift is conveyed in his letter to Mrs. Rathbone written on November 29, 1826:

“My Dear Good Mrs. Rathbone I have postponed writing to you day after day in hopes that I could do it as I longed to do. I mean much better than I am able, and more as I thought the occasion required, but it is all a vain attempt and I am at last reduced to thank you in humble words for the beautifull “Token of Esteem” you have sent me. Yes, I most sincerely thank you for the “Token” and the ‘esteem’ that you have so kindly expressed towards me in your precious note; those favours neither can or ever will be forgotten and, if you will permit me, suffer that I should say with all my heart: warmest wishes, may God Bless You. The first Impression of the seal was sent to my beloved wife the very night I received it from the hands of Professor Duncan, and it has given me much pleasure to hear some of my learned acquaintances here praise the workmanship and the Donor – It is not, I assure you, of little consequence to me here that the knowledge of the kind attentions received by you has been diffused through the medium of unknown friend[s] of mine. Where ever I go I am told “You became acquainted with the family Rathbone at Liverpool, Mr. Audubon,” but, my dear Madam, I dare not say any more. I know your gentle temper too well, and I will remove to other subjects.”

Letter from John James Audubon to Mrs. William Rathbone III, November 29, 1826

Audubon, John James and Daniel Patterson (editor), John James Audubon’s Journal of 1826: The Voyage to The Birds of America (2017)

Besides serving as a token of friendship between himself and the Rathbone family, this wax seal fob also represented a step forward for Audubon. Seal fobs were decorative accessories usually worn by men who had status and wealth. They were used to “sign” documents by sealing a personalized stamp into heated wax on letters and envelopes.

Scrapbook, 1920-1945

Julia Alves Clore Collection, JJA.1958.1

John James Audubon State Park Museum

Having his own seal to use with his official correspondence was a signal of respectability for Audubon. Imagine how satisfied he most likely felt when sending his first letter to Lucy with the wax impression made from his new seal. After all the criticism and mockery he had experienced in the United States for pursuing his art, what would it have meant to him to send her a letter signed with a seal made from one of his bird drawings? The seal was an indication that other people believed in him, valued his work, recognized that he was worthy of respect and admiration. Maybe Lucy and their sons could feel proud of him again…

This little object came to Audubon at a crucial moment when he would see whether The Birds of America was a fanciful scheme or an achievable project. A few days after Audubon opened his present from Mrs. Rathbone, production started on The Birds of America. Richard Rhodes writes that “about November 10, 1826, a day or two after Audubon received a letter from the Queen Bee enclosing his miniature wild turkey cock seal haloed with the motto “America My Country,” William Lizars began engraving Audubon’s lifesized drawing of a wild turkey cock looking back warily as it crossed a Louisiana canebrake for the first plate of The Birds of America” (Rhodes, 273).

John James Audubon State Park Museum Collection, JJA.1971.1

For many years, Audubon sealed all of his official correspondence with the wax seal fob given to him by Mrs. Rathbone. It remained in the family after his death in 1851 and eventually came to the Audubon Museum in Henderson, Kentucky with the loan (and later purchase) of the L.S. Tyler Collection in 1938. In Gallery C, the wax seal fob rests inconspicuously in a corner display case with Audubon’s life mask, gold watch, hairwork watch chain, a red wax impression from the seal fob, a set of six paintbrushes, and an 1835 copy of the “Ornithological Biography, or An Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America.”

Be sure to keep an eye out for Audubon’s wax seal fob the next time you make a visit to our museum at John James Audubon State Park. Every object here has a story to tell, even the smallest ones.

Stay safe and well this week!

This post was written by Heidi Taylor-Caudill, museum curator at John James Audubon State Park. Questions? Contact Heidi at 502-782-9716 or heidi.taylorcaudill@ky.gov.

SOURCES:

- Audubon, John James and Daniel Patterson (editor). John James Audubon’s Journal of 1826: The Voyage to The Birds of America. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2017.

- Audubon, John James. “My Seal!” John James Audubon State Park Museum Collection, undated.

- Herrick, Francis Hobart. Audubon the Naturalist: A History of His Life and Time. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1938.

- Rhodes, Richard. John James Audubon: The Making of an American. New York: Knopf, 2004.

- Steiner, Bill. Audubon Art Prints: A Collector’s Guide to Every Edition. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, 2003.

- Streshinsky, Shirley. Audubon: Life and Art in the American Wilderness. New York: Villard, 1993.