In our Object Spotlight series, we will take a closer look at the story behind an object from the collections of John James Audubon State Park Museum.

One of the rarest books in our museum collection — volume one of the Bien edition of The Birds of America (1858-1860) — represents the financial downfall of the Audubons in the early 1860s. How did this happen? A perfect storm of bad luck, illness, war, poor business decisions, and the expenses of a new printing process called chromolithography. Read on to hear the story behind the production of the Bien Edition and its disastrous consequences for the Audubon family.

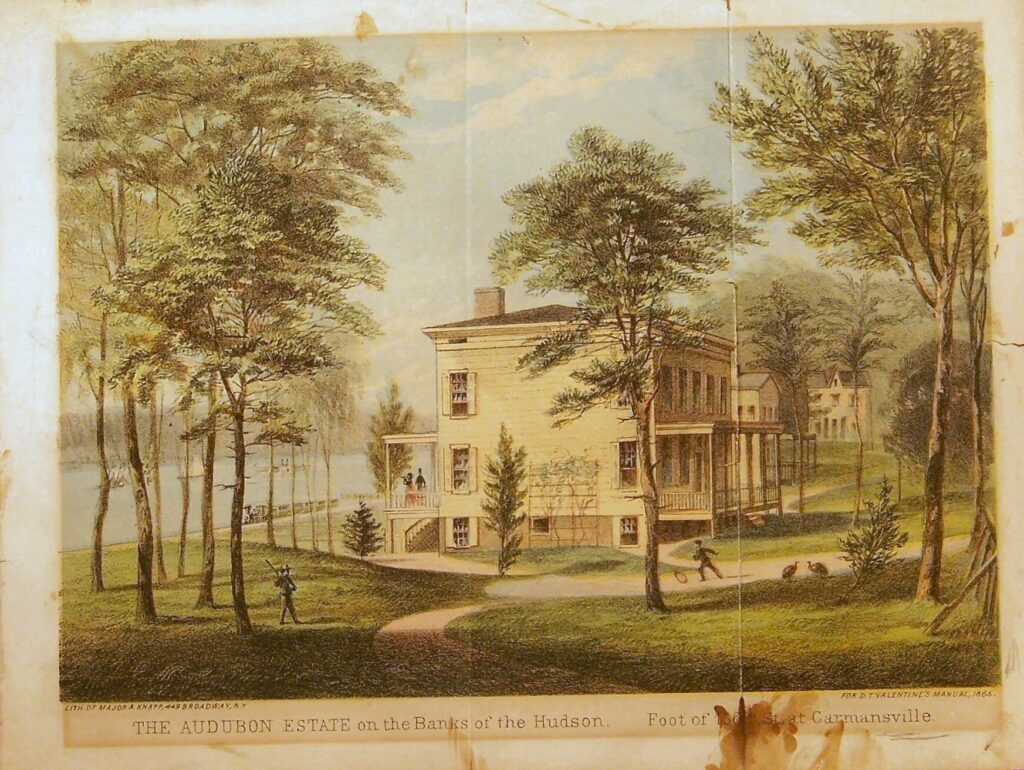

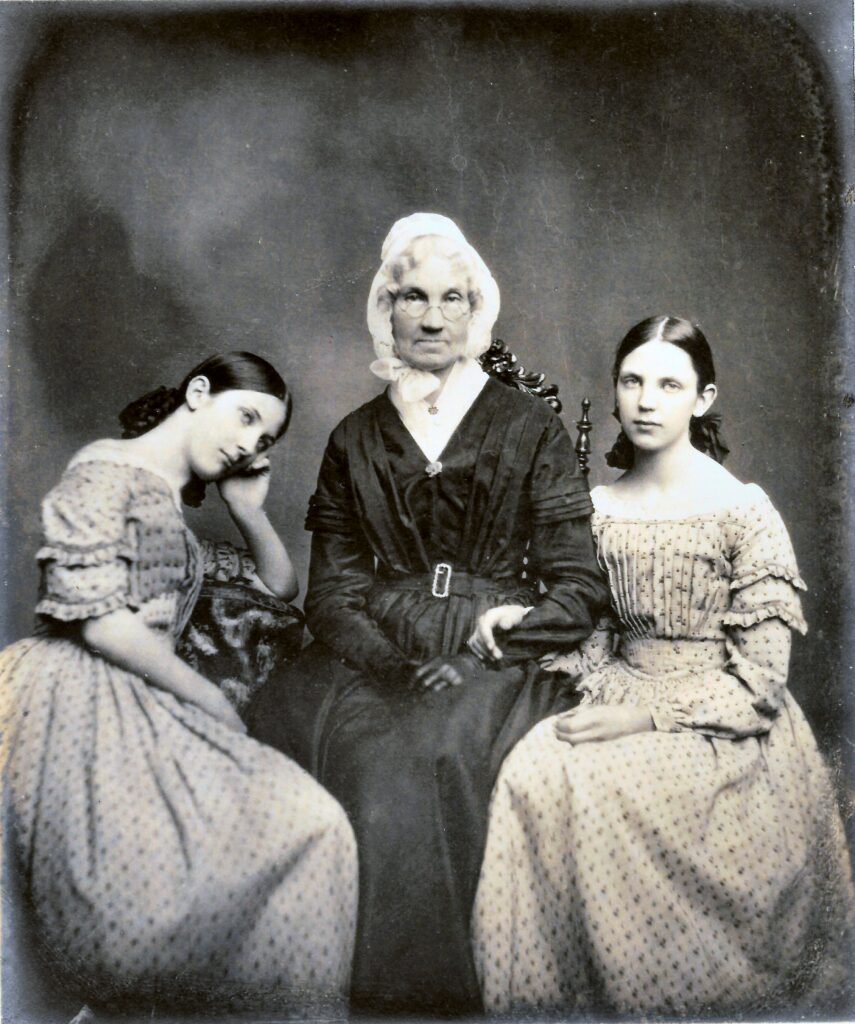

After John James Audubon’s death on January 27, 1851, his sons — Victor Gifford and John Woodhouse Audubon — knew they needed to turn to new business ventures in order to save the family fortune. Besides their own growing families, the brothers were responsible for their mother, Lucy, who had spent so many years struggling to support her children and herself while her husband worked on The Birds of America. In the decade that followed Audubon’s death, Victor and John Woodhouse attempted several projects, including completing their father’s last work, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, publishing smaller editions of The Birds of North America and the Quadrupeds, building a foundry, and making a trip to participate in the California Gold Rush. They also made questionable financial decisions such as the construction of new homes for themselves on the family’s property of Minnie’s Land, which took a great deal of money from the Audubon accounts.

The Audubon Estate on the Banks of the Hudson, 1865

Published by Major & Knapp

John James Audubon State Park Museum Collection, 1999.141

In an effort to generate income, Victor insisted that Lucy move in with his family so that the brothers could rent out her house. Soon after this, Victor injured his spine in an accident. Though he tried to remain active, he eventually became an invalid. His mother, now 70 years old, cared for him for the next three years. She also returned to the work that had sustained her and the boys in the past, teaching school in Victor’s house with her grandchildren and the children of neighbors as students.

John James Audubon State Park Museum Collection, 1945.9

John James Audubon State Park Museum Collection, 1944.5

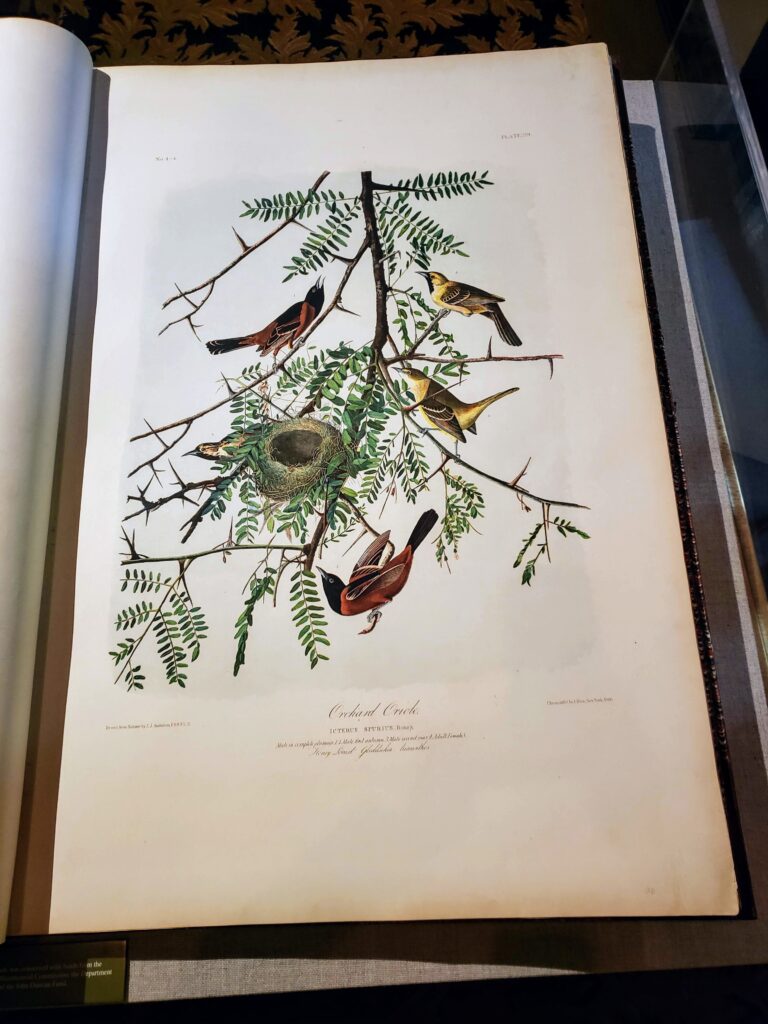

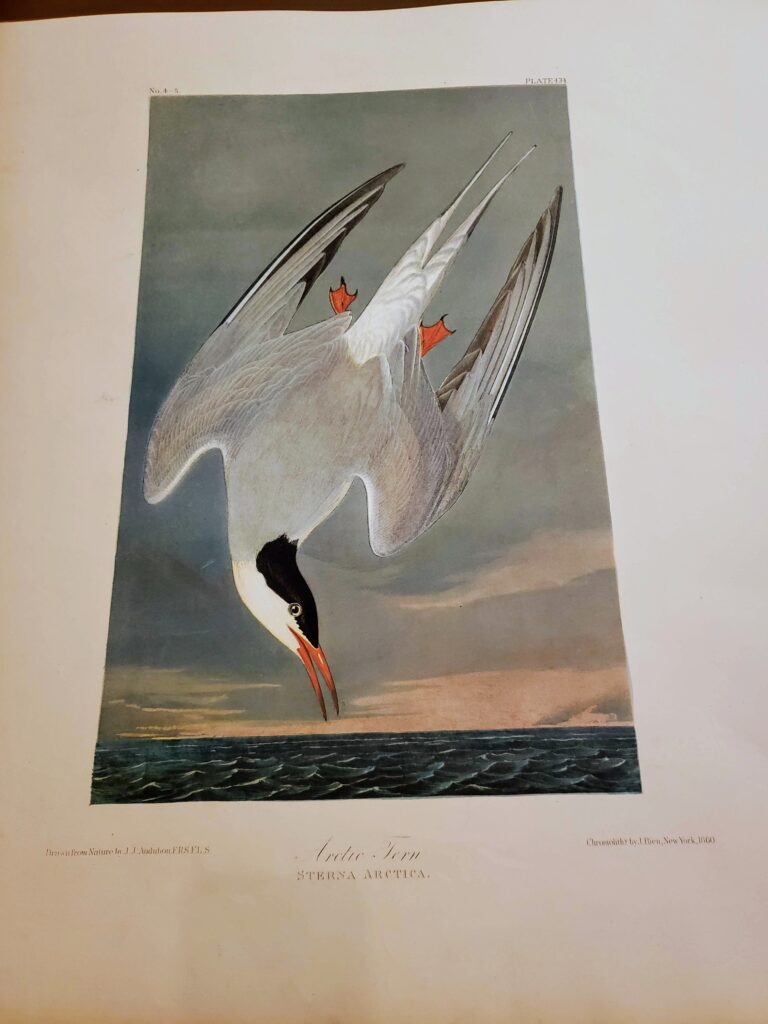

John Woodhouse felt the burden of supporting two families and his mother fall heavily on his shoulders. In 1858, he and Victor launched a venture to reproduce their father’s double elephant folio of The Birds of America at full size and in color using a new printing process called chromolithography. The brothers thought chromolithography — which produces a colored image from many applications of lithographic stones, each tinted with a different color — would produce better images at a reduced cost than the original Robert Havell, Jr., engravings. John Woodhouse partnered with a publisher, Roe Lockwood Company of New York, to finance and manage the project, and hired American lithographer Julius Bien to do the printing. The projected costs of making the prints were so high that John Woodhouse asked Lucy to co-sign the contract with Roe Lockwood Company as a guarantor. This would prove to be a terrible choice on Lucy’s part, leading to the eventual loss of nearly everything that she and her husband had worked so hard for.

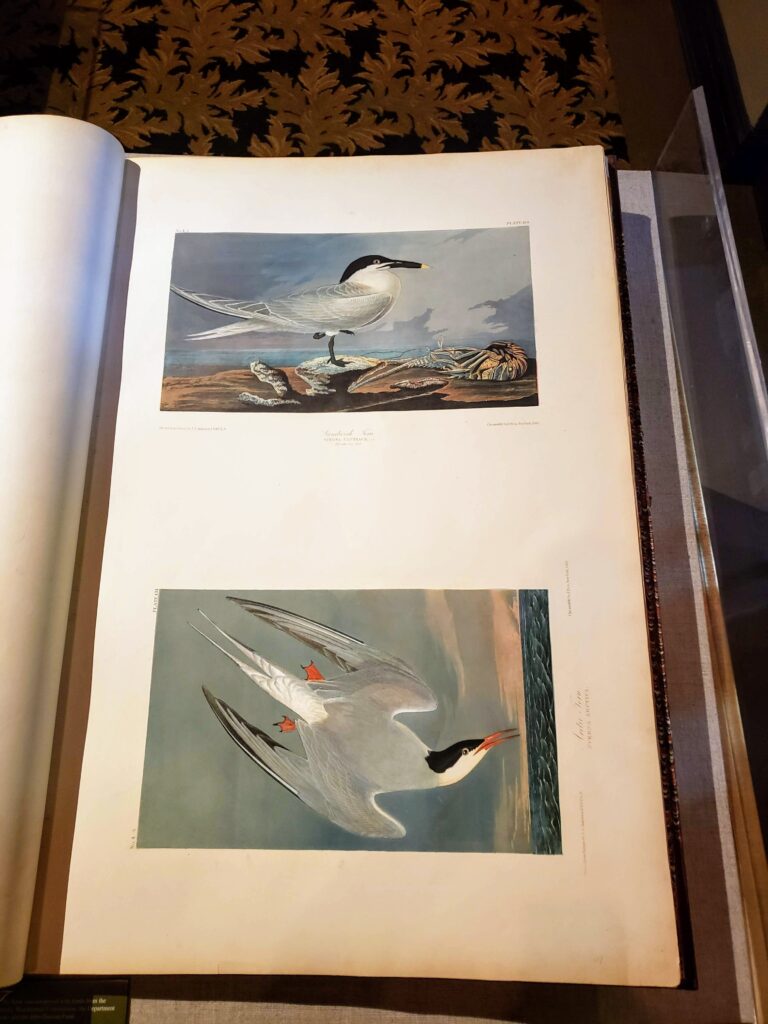

Like John James Audubon did with the original edition of The Birds of America, John Woodhouse planned to secure subscribers to the Bien edition as a way to pay back production costs and hopefully generate a profit. Each issue of the Bien prints would provide a subscriber with 7 sheets (pages) of 10 images:

- 2 sheets with 1 large image each

- 2 sheets with 1 medium image each

- 3 sheets with 2 small images each

John Woodhouse was able to print 150 birds on 105 sheets from The Birds of America before the project had to end. This was enough to bind together one volume. There were to have been three volumes. According to Bill Steiner, an expert on Audubon prints, only around 100 copies of the 105 sheets were ever produced.

In his 2003 book, Audubon Art Prints: A Collector’s Guide to Every Edition, Steiner explains the reasons for the Bien edition’s failure:

“A number of factors doomed the Bien edition. First, the Civil War loomed on the horizon, and many of the southern subscribers canceled. Second, John Woodhouse was simply a poor business manager and salesman. Third, the sheer expense of preparing the huge printing stones, and then experimenting until the color mixes were right, probably meant that a large number of prints had to be made and sold to reach a break-even point. Another distinct possibility is that the subscribers were just not happy with the quality of the prints because, compared to the Havell prints, most were not very well made. The Bien edition ended in failure, and the debt incurred in production costs bankrupted the Audubons.”

Bill Steiner, Audubon Art Prints: A Collector’s Guide to Every Edition (2003), page 74.

Around the ending of the project, on August 18, 1860, Victor died at his home. He was 51 years old. His brother and mother felt his loss deeply, and their grief was made worse by the creditors who placed liens on their property as it became apparent the Bien edition would not be completed. John Woodhouse now faced supporting three households: his wife and 7 children, his brother’s wife and 6 children, and his elderly mother. As he worried over the threat of bankruptcy, he scoured the Audubon estate for anything he could convert to cash.

Rev. Dr. Victor Dowdell Collection, 1961.4

John James Audubon State Park Museum

John Woodhouse’s daughter, Maria Audubon, described her father’s complete physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion at this time:

“During this long period of my uncle’s illness all the care of both families devolved on my father. Never a “business man,” saddened by his brother’s condition, and utterly unable to manage, at the same time, a fairly large estate, the publication of two illustrated works, every plate of which he felt he must personally examine, the securing of subscribers and the financial condition of everything — what wonder that he rapidly aged, what wonder that the burden was ovewhelming! After my uncle’s death matters became still more difficult to handle, owing to the unsettled condition of the southern states where most of the subscribers to Audubon’s books resided, and when the open rupture came between north and south, the condition of affairs can hardly be imagined, except by those who lived through similar bitter and painful experiences.”

Francis Hobart Herrick, Audubon, the Naturalist, volume II (1938), pages 295-296.

The stress of the situation was too much for him. John Woodhouse died on February 18, 1862 at the age of 49.

Lucy was now alone at 75 years old without her husband, sons, or money. In 1863, to repay debts and provide funds for the family, Lucy sold Minnie’s Land and the original watercolor drawings for the plates of The Birds of America. She spent her last years living with grandchildren and other relatives, dying on June 18, 1874 at her youngest brother’s home in Shelbyville, Kentucky.

In 2003, Bill Steiner estimated that there may only be 30 complete copies of the Bien edition still in existence. We are lucky to have one of those few copies in our collection at the John James Audubon State Park Museum. It was donated to the museum on June 28, 1938 by the Kentucky State Library in Frankfort. In 1992, the book was conserved with funds from the Kentucky Bicentennial Commission, the Department of Parks, and the John Duncan Fund. This conservation work was undertaken to help ensure the long-term survival of the rare prints in the book.

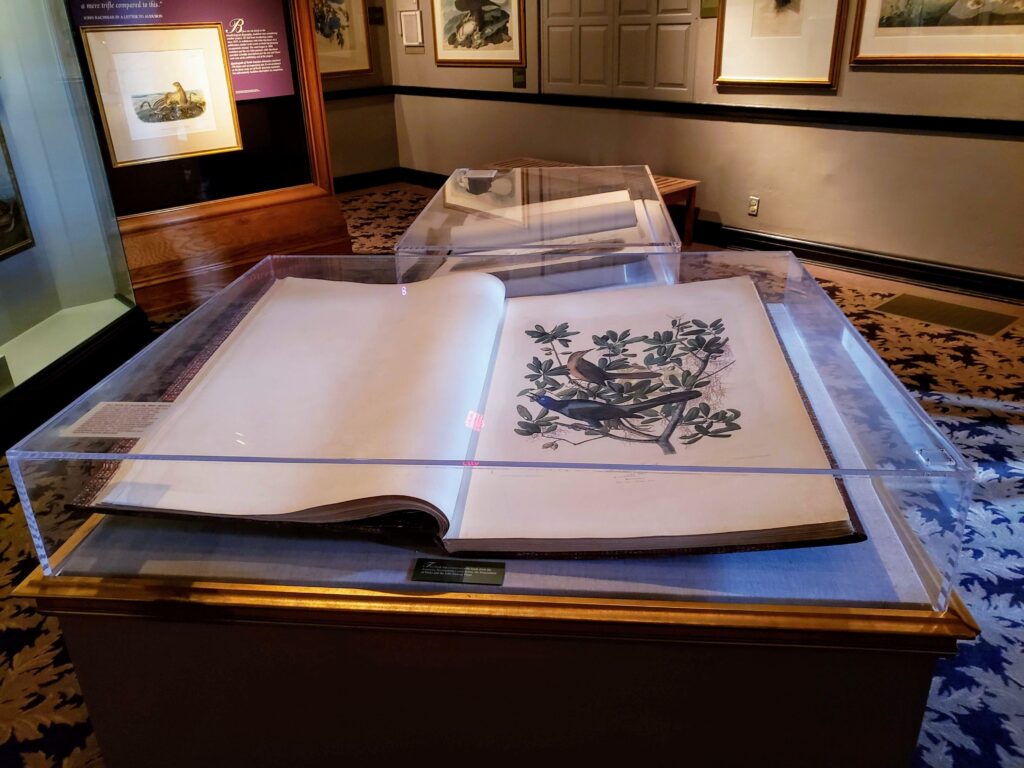

The Bien edition is usually on display in Gallery A near the entrance to the museum tower. Each month, we turn the pages of this book as a preservation measure to reduce long-term light damage to the prints. An added bonus is that by doing this, new images from the book can be shared with our visitors every few weeks. Below is the medium-sized image that was on display in April (regrettably, to an audience of just one — me) and the two small images that were revealed when I turned the pages this week.

John James Audubon State Park Museum Collection, 1938.307

I look forward to the day that we can again share the Bien edition and our other wonderful Audubon objects with visitors in the museum. In the meantime, we will continue to share our collection virtually through social media and this blog. Consider following us on:

- Facebook: @johnjamesaudubonstatepark

- Twitter: @JJAStatePark

- Instagram: @audubon_state_park

Stay safe and well.

This blog post was written by Heidi Taylor-Caudill, Curator of the John James Audubon State Park Museum.

SOURCES:

- DeLatte, Carolyn E. Lucy Audubon: A Biography. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2008.

- Herrick, Francis Hobart. Audubon the Naturalist: A History of his Life and Time. New York, NY: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1938.

- Souder, William. Under a Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of the Birds of America. Minneapolis, MN: Milkweed Editions, 2014.

- Steiner, Bill. Audubon Art Prints: A Collector’s Guide to Every Edition. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, 2003.