In our Recent Research series, curator Heidi Taylor-Caudill shares answers to questions sent to the Audubon Museum about John James Audubon and his family, the museum’s collection, and the history of John James Audubon State Park.

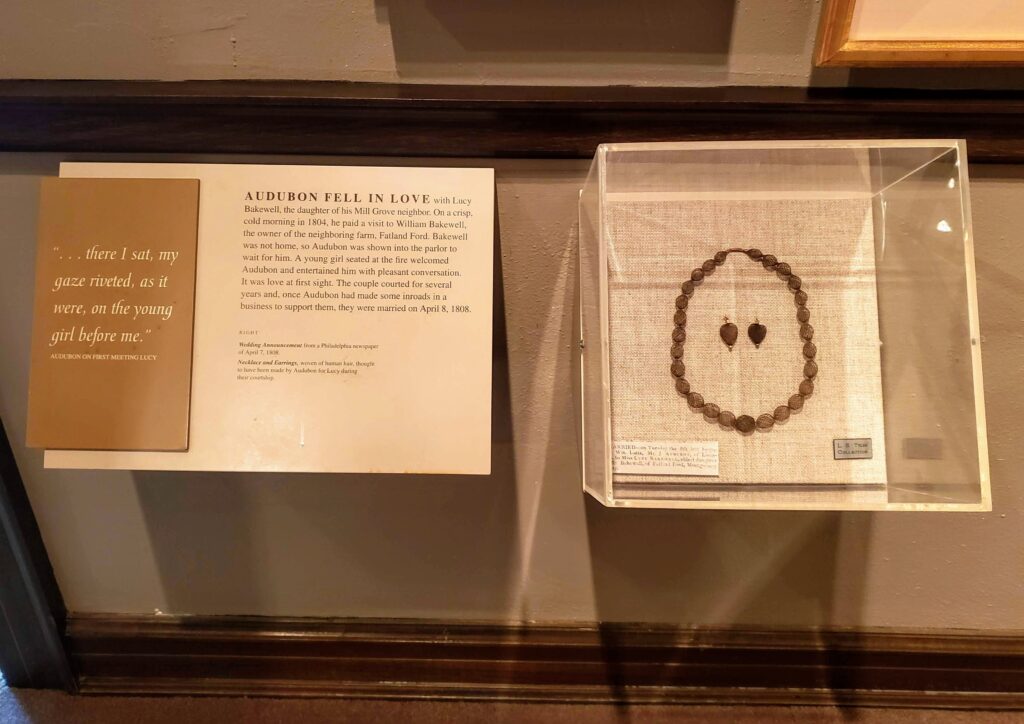

Walking through the museum galleries earlier this week, I noticed three visitors huddled around the small display case containing a necklace and set of earrings made out of human hair. One person was on their knees trying to get a closer look at details of the jewelry through the side of the case. The other two people were speaking in low tones to each other, asking, “is it real?” and “that’s kind of gross, why would someone make something like that?” I wasn’t surprised — these are common reactions among our visitors of all ages when they first notice the hairwork on display near the entrance to Gallery A. The necklace and earrings, which are said to have been made by John James Audubon from his own hair and given to Lucy Bakewell during their courtship, often stops people in their tracks.

Slowing to a stop, I said, “Oh, you’ve noticed the hairwork! What do you think about it?” I waited to see whether they wanted to interact with me. Some visitors are open to having a conversation, others desire to be left alone. It turned out that these three visitors were eager to talk about this unusual jewelry.

None of them had heard of hairwork so it was a shock to see a necklace and set of earrings made from human hair. One person told me, “I just think it’s really weird and creepy.” Another person picked up that thought and commented, “I don’t understand how anyone would want to wear jewelry made out of hair. What was Audubon thinking giving something like that to the girl he liked? I would be running away if someone did that with me!” I nodded as I listened, also sensing a bit of insecurity and an unspoken question in the air: “are my feelings and thoughts about these objects valid?” Before answering their questions, I wanted to reassure these visitors that it was OK to connect with the necklace and earrings on their own terms. They didn’t need me to tell them how to experience the hairwork, but I could encourage them to think more deeply by offering additional details about the jewelry and its meaning in John James Audubon’s culture.

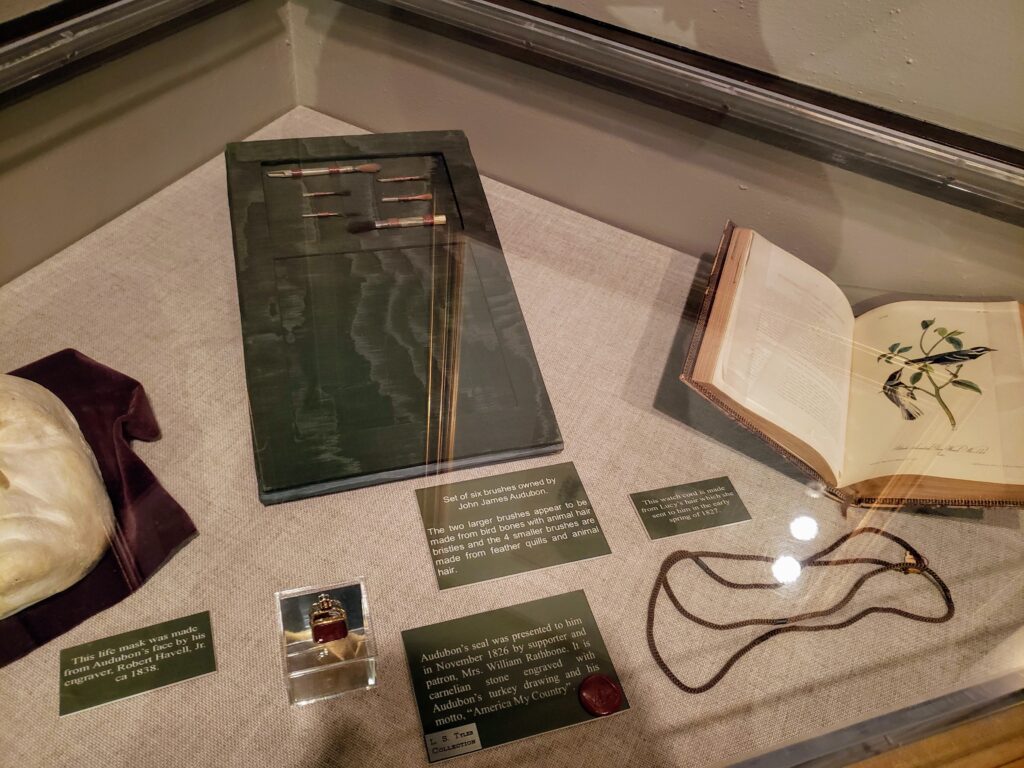

In this post, I will talk about some of the hairwork in our collection and how it can help us understand the social reality in which Audubon and his family lived. I will also share the examples of hairwork in our museum’s collection. Some of these objects are currently on display in the galleries; others are held in storage. With the exception of one brooch, all of the hairwork came to the museum through the Tyler family who are descendants of John James and Lucy Audubon through their eldest son, Victor Gifford. Most of the jewelry is said to contain hair from John James, Lucy, Victor Gifford, and/or John Woodhouse Audubon, except for a brooch owned by Victor Gifford’s sister-in-law and an unidentified bracelet clasp.

Interested in learning more about the hairwork in our collection? You can feel free to contact me with questions at 502-782-9716 or heidi.taylorcaudill@ky.gov.

What is Hairwork?

Hairwork — jewelry or art made from human hair — has been practiced throughout recorded history, but the concept became especially popular in the 18th and 19th centuries. Throughout that period, people used hairwork in mourning practices and exchanged items containing hair as sentimental gifts. As a part of the body that is slow to decay, hair could be incorporated into jewelry to be worn as a keepsake of another person. Watch chains, cuff links, necklaces, bracelets, rings, earrings, and brooches all provided a means to hold close a piece of that loved one, even when separated from you by distance or death.

Godey’s Lady’s Book, a popular magazine for American women in the 19th century, described the appeal of hair as a keepsake in this way:

“Hair is at once the most delicate and lasting of our materials and survives us like love. It is so light, so gentle, so escaping from the idea of death, that, with a lock of hair belonging to a child or friend, we may almost look to to Heaven and compare notes with angelic nature, may almost say: ‘I have a piece of thee here, not unworthy of thy being now.'”

Godey’s Lady’s Book, volume 60 (1860), page 380.

This may sound strange to us today when digital technology allows us to communicate easily with friends and family on the other side of the world, travel is relatively easy, fast, and safe, and a multitude of photographs help us remember the faces of those who have died. Remember that these were really not options for people in John James and Lucy Audubon’s time. Hairwork offered a way for them to demonstrate their relationships and maintain a sense of connection. These two ideas — relationships and connection — can be explored through an example of hairwork and two letters from our museum’s collection.

Mourning and Remembering

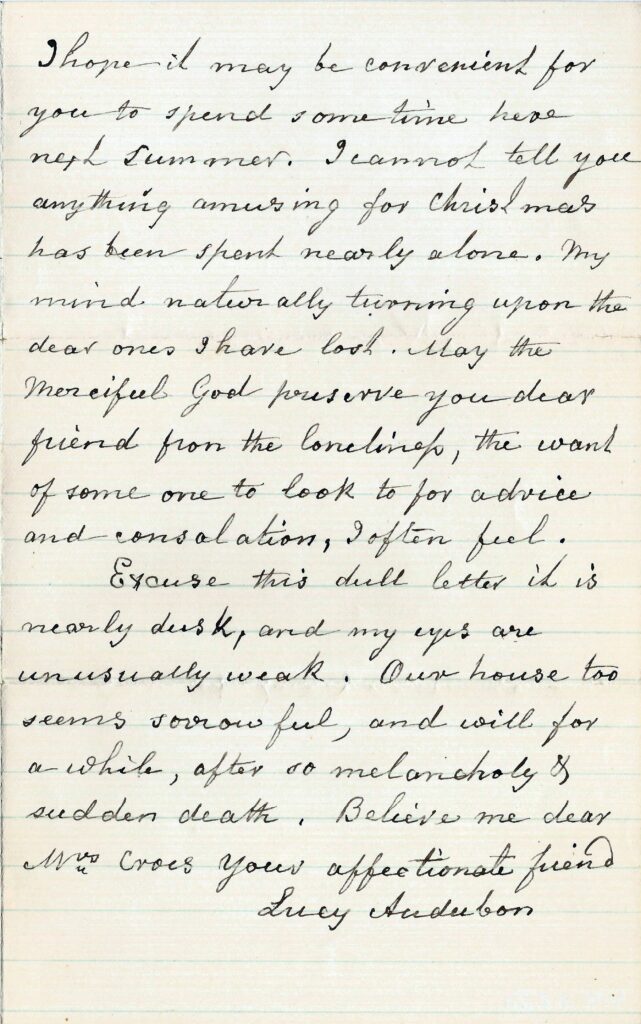

The three most important people in Lucy Bakewell Audubon’s life were almost certainly her husband, John James Audubon, and their two sons, Victor Gifford and John Woodhouse Audubon. She outlived them all. John James Audubon died on January 27, 1851 at their home in New York. Around 1856, Victor Gifford experienced an accident that left him an invalid. Lucy cared for him for three years before he passed away in 1860. Two years later on February 18, 1862, John Woodhouse died after an illness. Lucy was left alone in a difficult situation. Now responsible for large debts incurred by her sons and desperate to find money for the family, she sold their property and the original watercolor drawings of The Birds of America. Lucy spent the rest of her life living with grandchildren and other relatives. She died at the age of 87 on June 18, 1874 at her youngest brother’s home in Shelbyville, Kentucky.

In a letter written to a friend on December 27, 1863, Lucy describes her intense loneliness and remembrance of lost loved ones:

“I cannot tell you anything amusing for Christmas has been spent nearly alone. My mind naturally turning upon the dear ones I have lost. May the merciful God preserve you dear friend from the loneliness, the want of some one to look to for advice and consolation, I often feel.”

Lucy Bakewell Audubon, December 27, 1863

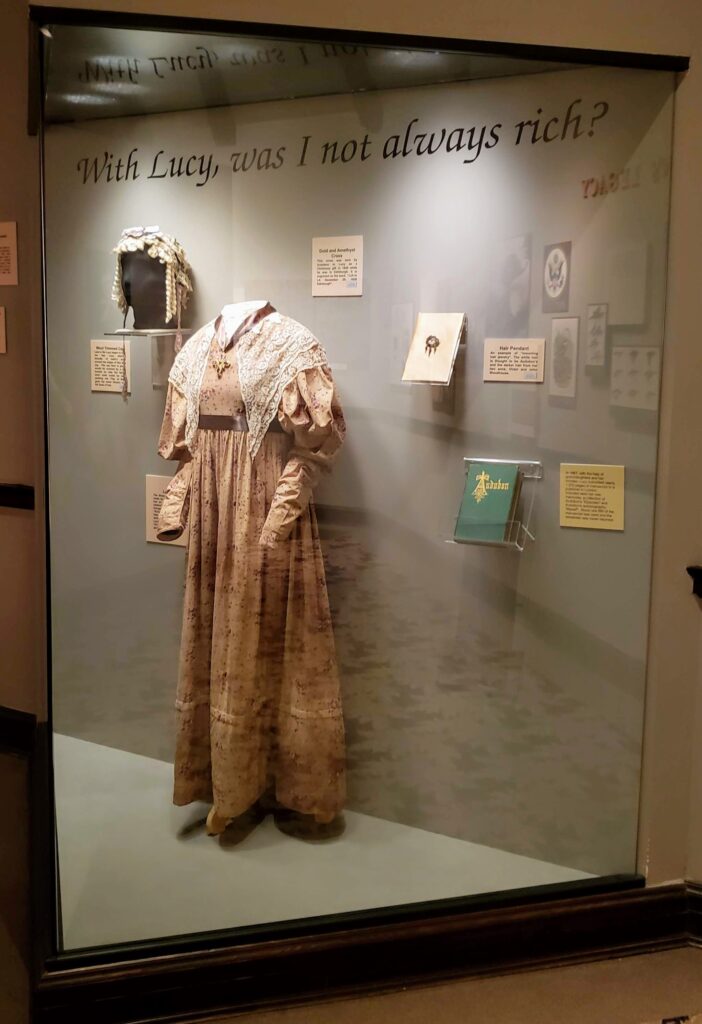

I think about Lucy’s despondent letter every time I see the hairwork brooch shown below. Once owned by Lucy and passed down through the Tyler family, this brooch is thought to hold the hair of John James, Victor Gifford, and John Woodhouse Audubon. It was a token of Lucy’s love and affection for her family that she could wear close to her heart, and in the years after their separation by death, could treasure as a lasting reminder of her husband and sons. I wonder how often she may have looked at this brooch, remembering their time together and reflecting on the course her life had taken.

The brooch is currently on display in Gallery A alongside Lucy’s dress and an 1875 copy of her book, The Life of John James Audubon, the Naturalist.

Right: John Woodhouse Audubon, Unfinished Portrait of Lucy Bakewell Audubon, undated. L.S. Tyler Collection, JJA.1938.1342.

A Grandmother’s Gift

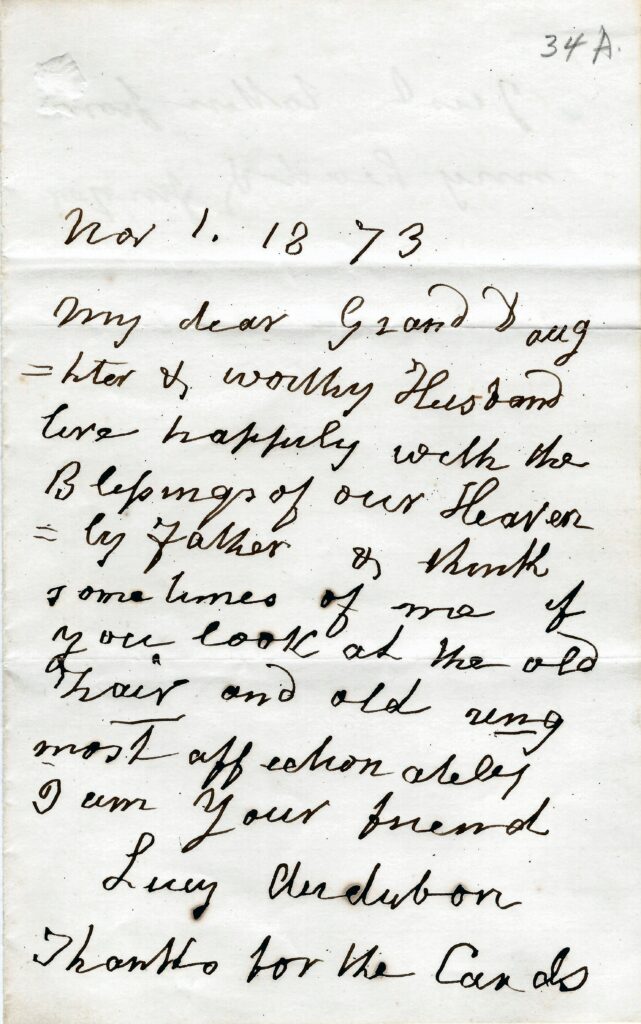

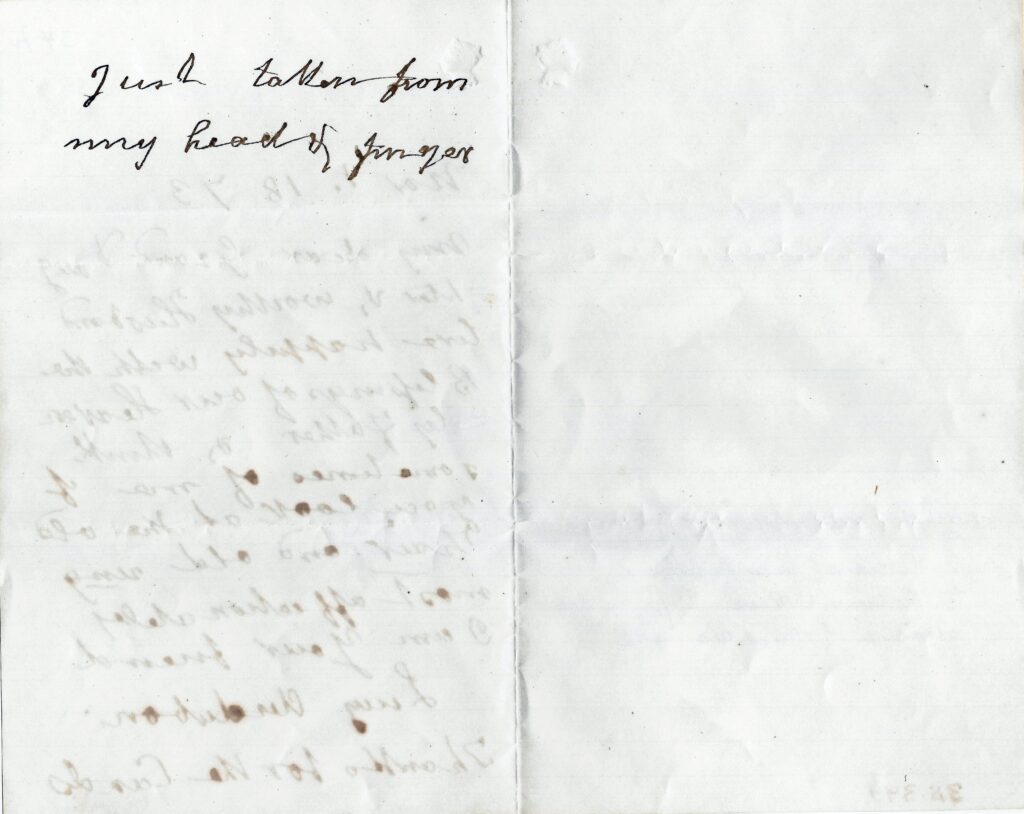

A few days before the marriage of her granddaughter, Delia Talman Audubon, and Morris Franklin Tyler on November 5, 1873, Lucy Audubon wrote a short, loving letter to them that mentions the gift of a piece of her hair and a ring. She asks the young couple to remember her with affection when looking at the lock of hair. On the back of the letter is a note about the hair and ring: “Just taken from my head & finger.”

“My dear granddaughter & worthy husband live happily with the Blessings of our Heavenly Father & think sometimes of me if you look at the old hair and old ring most affectionately I am Your friend Lucy Audubon.”

Lucy Bakewell Audubon, November 1, 1873

Top left, bottom: Letter from Lucy Bakewell Audubon to Delia Talman Audubon and Morris Franklin Tyler, November 1, 1873. L.S. Tyler Collection, JJA.1938.399.

Lucy wrote the letter to Delia and Morris in November 1873 — about eight months before her death — while living with relatives in Kentucky. In her words, “think sometimes of me if you look at the old hair,” Lucy implies that this gift of a literal piece of herself was meant to be a lasting reminder of her love and friendship. We’re not sure what happened to the hair mentioned in the letter. Maybe Delia fashioned it into a piece of jewelry or artwork? She obviously treasured the letter from her grandmother, and her descendants preserved it for many years before it came to our museum in 1938. Today, we value this document as a glimpse into Lucy Audubon’s enduring love for her family and her longing to maintain connections with them, even when separated by physical distance and later death.

Considerations

Maybe you’ve visited our museum and wondered about the hairwork on display in the galleries. What did you feel and think when you saw these objects? Did you know about hair jewelry before seeing them? Would you ever wear something made from human hair? And think about this — do you have sentimental objects that you keep to remember someone by?

Almost all of us have experienced a longing for the past, and objects can help evoke memories and draw us to each other. Though hairwork may seem odd and maybe disturbing to us today, remember that the motivation behind this art form was that of expressing relationships and connection. Anyone who has cherished a gift from a loved one, preserved an item as a reminder of home, or kept a favorite childhood toy can empathize with this impulse. As you look at the hair jewelry from our collection listed below, consider the reasons why these pieces were created and how they may have been viewed by the people who owned them.

Hairwork on Display

As of the publication of this post, the objects below are on display in the Audubon Museum galleries.

John James Audubon (1785-1851) (attributed to)

Necklace and Earrings, circa 1806

Gold, human hair

L.S. Tyler Collection, JJA.1938.1197 (necklace) and JJA.1938.1198a-b (earrings)

Current Location: Gallery A

The Tyler family believes that John James Audubon made this necklace and earring set for his neighbor, Lucy Bakewell, during their courtship in Pennsylvania.

The necklace is made from chestnut-colored human hair that has been finely braided and woven into a series of 27 bead like shapes. These beads appear to be waxed and vary in size. The necklace is held together with a gold clasp. The two heart-shaped earrings are made from chestnut-colored human hair that have been waxed, finely braided, and woven. A gold bead decorates the bottom tip of each earring and a small ring is attached to the top.

Lucy Bakewell Audubon (1787-1874) (attributed to)

Watch Cord, circa 1800-1850

Gold, metal, human hair

L.S. Tyler Collection, JJA.1938.1200

Current Location: Gallery C

This long, woven watch cord is made with dark human hair. It has a gold cylindrical clasp and other smaller metal tubes, possibly joining two sections. Lucy Bakewell Audubon is said to have made this cord from her own hair and sent it as a gift to her husband in the spring of 1827.

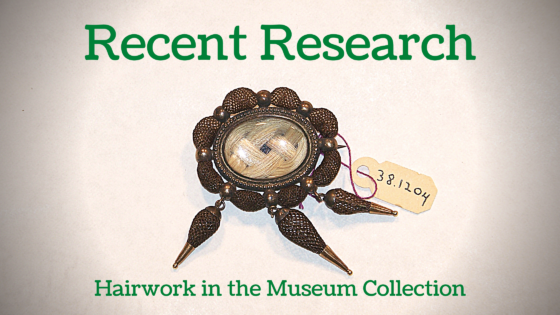

Unknown maker

Brooch, circa 1850

Gold, glass, human hair

L.S. Tyler Collection, JJA.1938.1204

Current Location: Gallery A

This brooch is made with twisted and woven human hair. It is believed that these are the hairs of John James Audubon and his sons, Victor Gifford and John Woodhouse Audubon.

Braided white hair is set in an oval gold setting with a glass cover. Dark hair twisted into an open lattice form is woven through rings attached to the central setting. Three beads of similar dark twisted hair dangle from the bottom of the brooch. The hair beads have gold end caps.

Works in Storage

As of the publication of this post, the objects below are not on display in the Audubon Museum galleries, but located in storage.

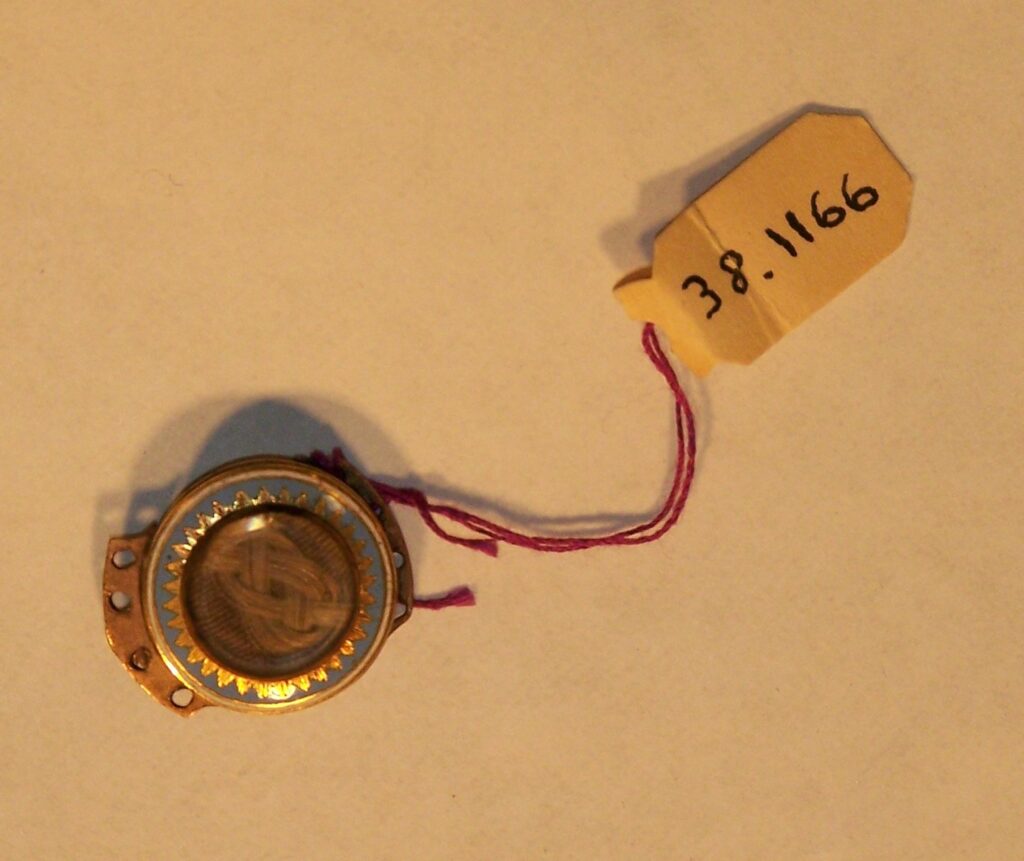

Unknown maker

Bracelet Clasp, circa 1900

Gold, enamel, glass, human hair

L.S. Tyler Collection, JJA.1938.1166

Current Location: Storage

This bracelet clasp features a small section of braided gray hair under a circular piece of glass, which is framed in a circular enamel piece with a white, blue, and gold border. The entire piece is secured within a circular metal setting with two narrow plates, each with four holes, extending from opposite sides of the clasp.

Unknown maker

Brooch, circa 1880

Gold, glass, metal, human hair

L.S. Tyler Collection, JJA.1938.1202

Current Location: Storage

This brooch belonged to Eliza Mallory, sister-in-law of Victor Gifford Audubon. The piece is oval in shape and features a braided gold frame, a clear glass front, and gold backing. Beneath the glass is a lock of loosely-braided light brown or dark blonde hair resting on top of what appears to be tightly-braided dark brown hair. “E. Mallory” is inscribed in cursive on the back of the brooch. The brooch pin is missing.

Unknown maker

Brooch, circa 1864

Brass, glass, human hair

Mrs. W. H. Washburn Collection, JJA.1945.4

Current Location: Storage

Mrs. W. H. Washburn claimed that this brooch belonged to Lucy Bakewell Audubon.

The small, oval pinchbeck brass brooch features coils of light brown and dark brown hair encased beneath a glass cover. The light brown hair is braided around the dark brown hair. Beneath these is a section of braided dark brown hair. The brass case is beveled around the edges, giving it a diamond pattern. The back of the brooch is smooth and the straight pin is held in place with a simple hook.

This post was written by Heidi Taylor-Caudill, museum curator at John James Audubon State Park. Questions? Contact Heidi at heidi.taylorcaudill@ky.gov.

SOURCES:

- Audubon Park Alliance. “The Audubons of Minniesland.” Last modified 2020. http://www.audubonparkny.com/audubonfamily.html.

- DeLatte, Carolyn E. Lucy Audubon: A Biography. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2008.

- “Hair Ornaments.” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine, 1860. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d00322043u

- Peters, Hayden. “A History of Hairwork, Part 1: Introduction.” Art of Mourning (blog), March 9, 2010. https://artofmourning.wordpress.com/2010/03/09/an-overview-of-the-history-and-industry-of-hairwork-part-1/.

- Peters, Hayden. “A History of Hairwork, Part 2.” Art of Mourning (blog), March 15, 2010. https://artofmourning.wordpress.com/2010/03/15/118/.