In our Object Spotlight series, museum curator Heidi Taylor-Caudill takes a closer look at the story behind an object from the collections of John James Audubon State Park Museum.

As I look at objects in our collection, I ask myself: what stories can they tell?

One of the challenges of being a museum curator is working with things that have been removed from their original context and made part of a collection. Often the person who collected an object is no longer around for questions. You hope that enough information has been kept in records to reconstruct the conditions in which that object was made, used, and owned, so that you can talk about its history and better understand the potential stories it could tell museum visitors. Sometimes, though, there just isn’t much information available. This is when you have to play detective and do your research.

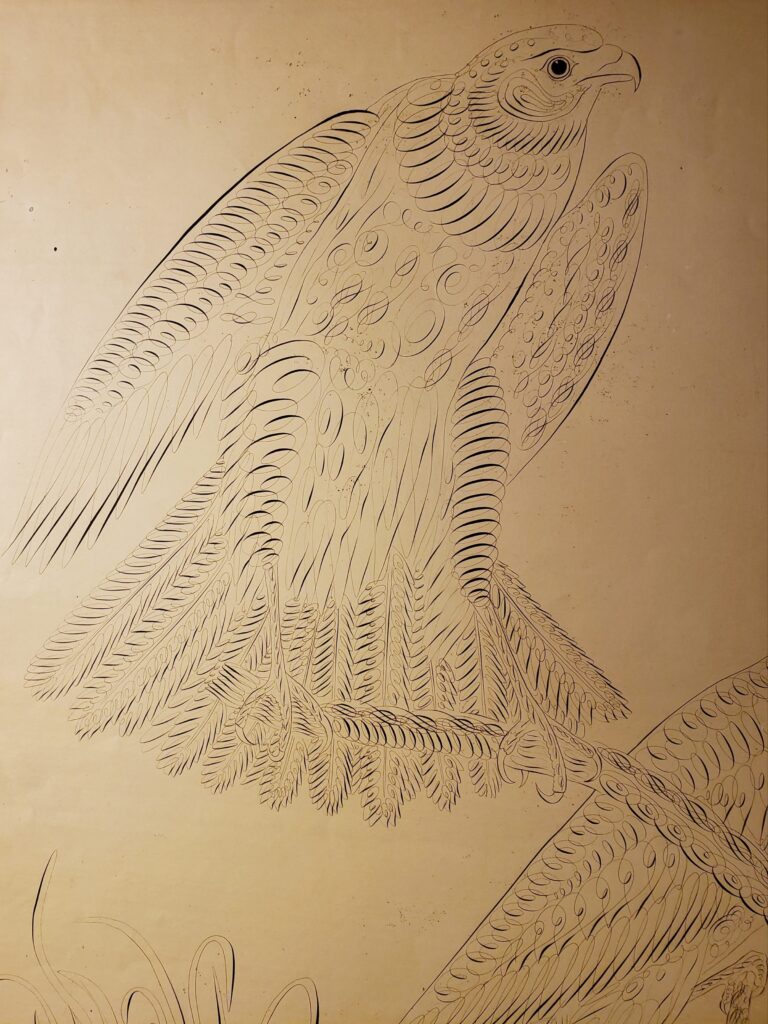

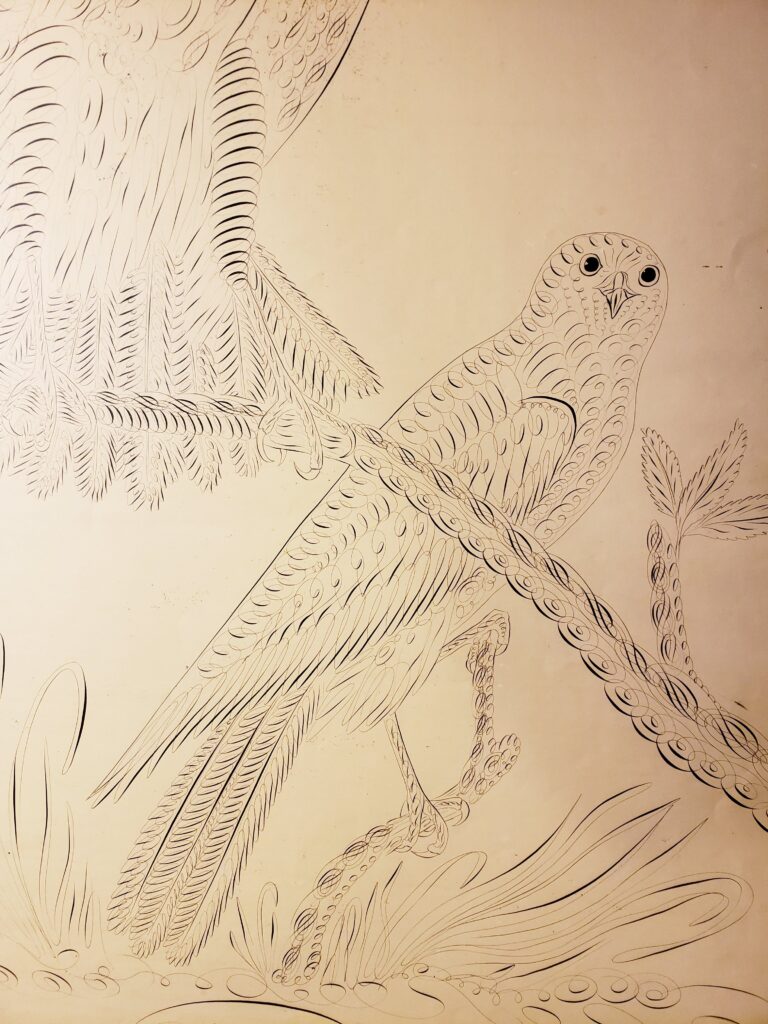

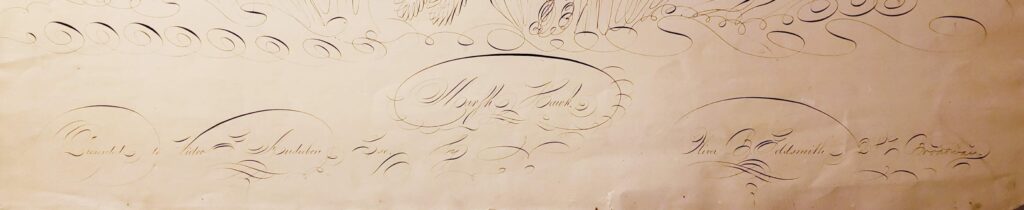

A few months ago I took a large work on paper (see below) out of our flat files to examine more closely. Titled Marsh Hawk, it is a gorgeous pen and ink drawing of two birds resting on branches. The forms of the birds and the plants are composed of intricate swirls, loops, and curves. At the bottom is the name Victor G. Audubon, the title, the name Oliver B. Goldsmith, and an address. I was immediately intrigued. What was the story behind this drawing and how did it end up in our museum?

L. S. Tyler Collection, JJA.1938.1262.

Pen and ink on paper, 30.187″x 22″

In today’s Object Spotlight post, I will share findings from my research into the history behind the Marsh Hawk drawing and some theories about the artist’s motives for creating it. We will also look more closely at the composition of the Marsh Hawk and examine its connection to John James Audubon’s masterwork The Birds of America. In the end, we will explore the idea of this drawing’s value for the Audubon Museum and answer the question of why we continue to preserve it.

Interested in learning more about the Marsh Hawk? You can feel free to contact me with questions at 502-782-9716 or heidi.taylorcaudill@ky.gov.

The Artist

Oliver B. Goldsmith (1815-1888) was considered one of the best offhand penmen in the United States during his lifetime. Born in 1815 in Cutchogue, Long Island, Goldsmith left home at the age of 15 to become a store clerk in New York City. By age 22, he owned the largest dry goods store on the east side of the city. He lost that business in the financial crisis of 1837. Broke and needing to reinvent himself, Goldsmith started studying penmanship under Isaac F. Bragg. He discovered a talent for offhand flourishing, a combination of drawing and calligraphy that was highly in demand at the time for advertisements, official documents, certificates, and the title pages of books. In 1838, Goldsmith opened a school for penmanship in Brooklyn. An advocate for using metal pointed pens in writing and decoration, he published Goldsmith’s Gems of Penmanship in 1844 with examples made with metal pens. After a long career as a professor of penmanship, Goldsmith died in New York City on April 28, 1888.

The Work

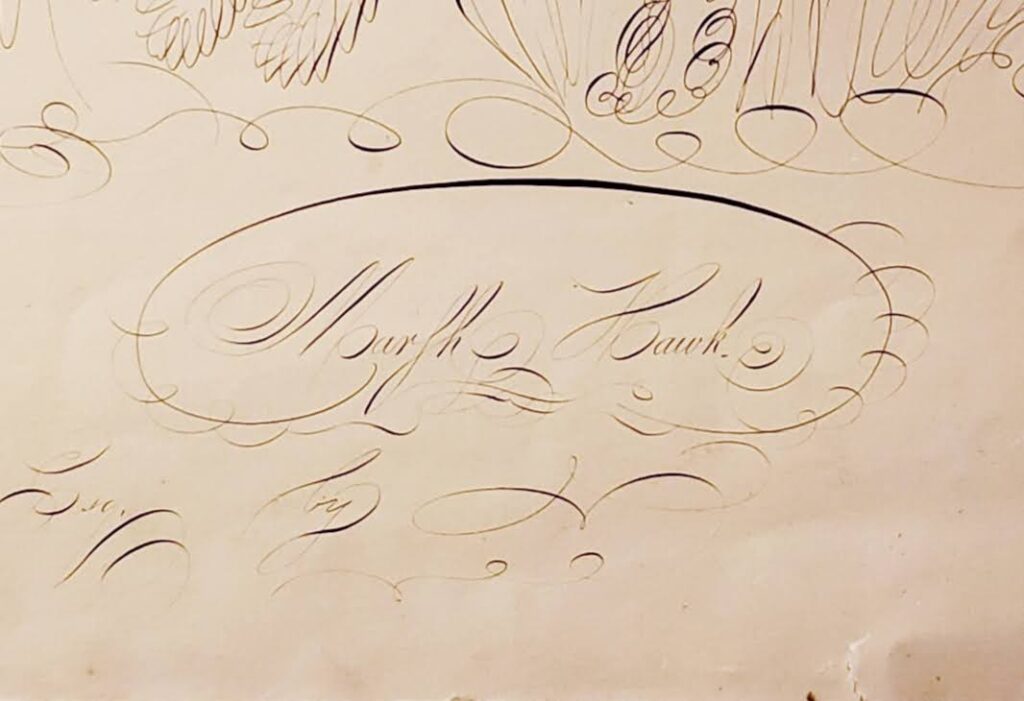

Goldsmith’s large calligraphic drawing, Marsh Hawk, is a demonstration of his creative and technical skills in offhand flourishing. Incredibly difficult to accomplish without lots of practice, confidence, and an eye for design, pictures made from flourishes are often done in one shot. The artist controls the motion of their arm and hand to precisely and rapidly draw graceful strokes, curves, and ovals across the surface of the page. This combination of form and movement produces intricate designs.

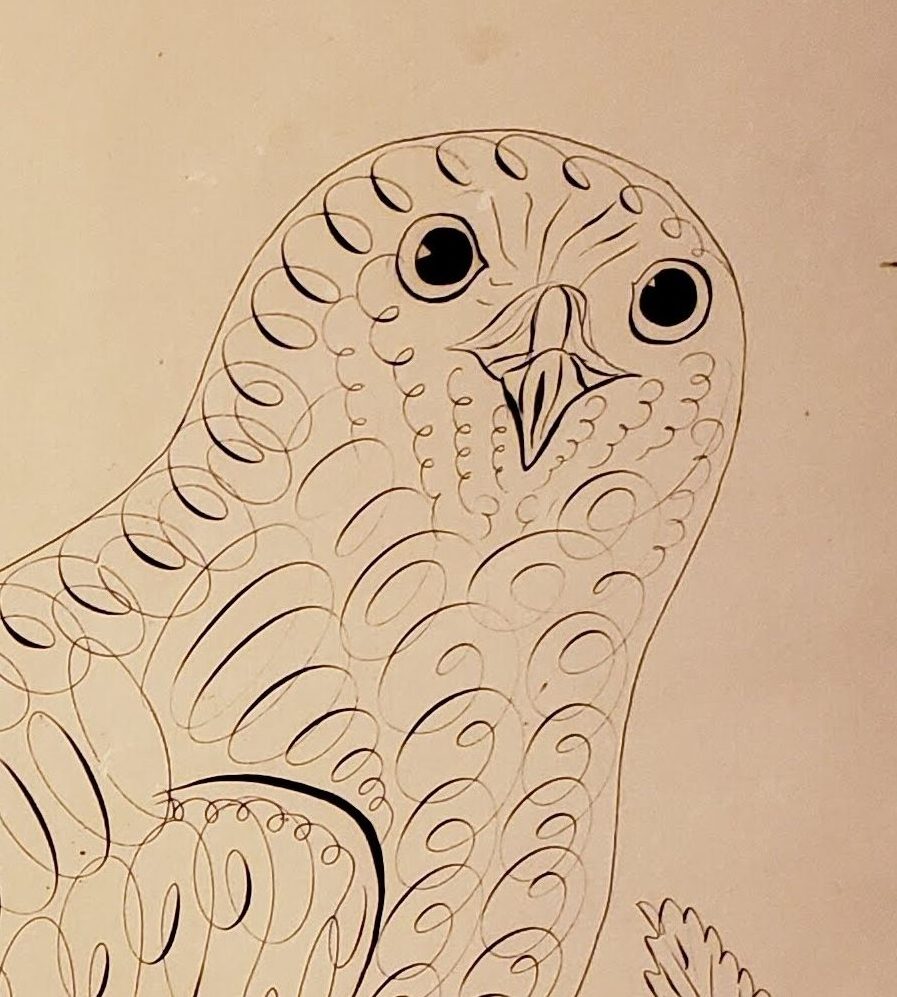

In the close-up photos of Goldsmith’s Marsh Hawk above, you can see how he uses curved lines, loops, spirals, and ovals to create the different shapes and textures of wings, feathers, beaks, leaves, and branches. The varying thickness of the ink (such as on the feathers and the beaks) adds depth and dimension to the drawing by suggesting shadows and highlights. He implies texture through spirals and curves such as the tightly coiled, repetitive spirals that evoke the rough “feel” of the bark on the branches. You can sense the sharpness of the birds’ talons through the curving lines that meet in points and the spiky edges of the leaf through the little arched lines outlining a leaf-shape. What else can you notice about his use of line and shape in these photos?

The focal points of the piece are the dark eyes of the two birds, which seem to watch you with caution and a bit of curiosity. Goldsmith uses the visual weight of the black circles representing the eyes to draw your attention to the birds’ expressions, pulling you deeper into the work. Each circle is almost solid black except for a small triangular section that he leaves uninked, imitating the reflection of light on the surface of the pupil. The thickly drawn outline of a circle around the black pupil further emphasizes the eye as a point of interest. As you, the viewer, look at the birds, they return your gaze.

The Inspiration

What motivated Goldsmith to create this beautiful piece of artistic penmanship? There are a few clues at the bottom of the page.

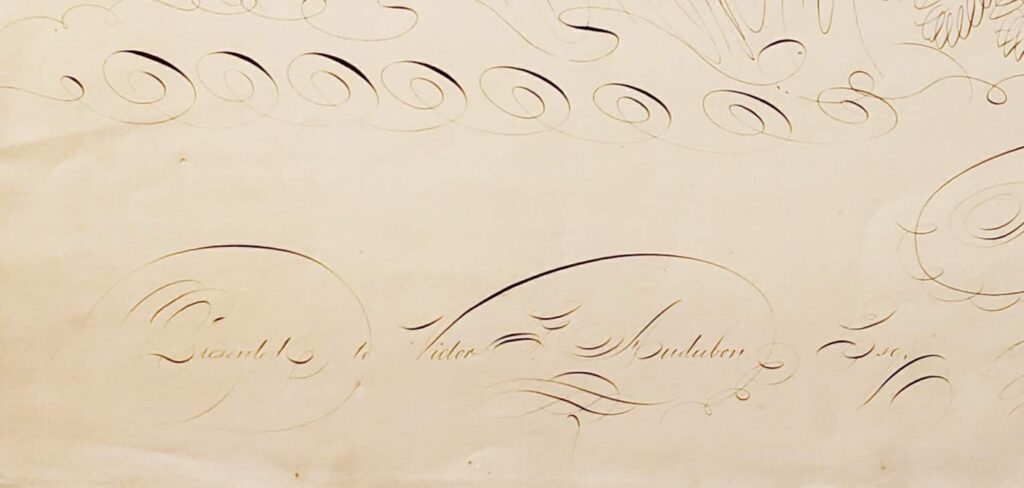

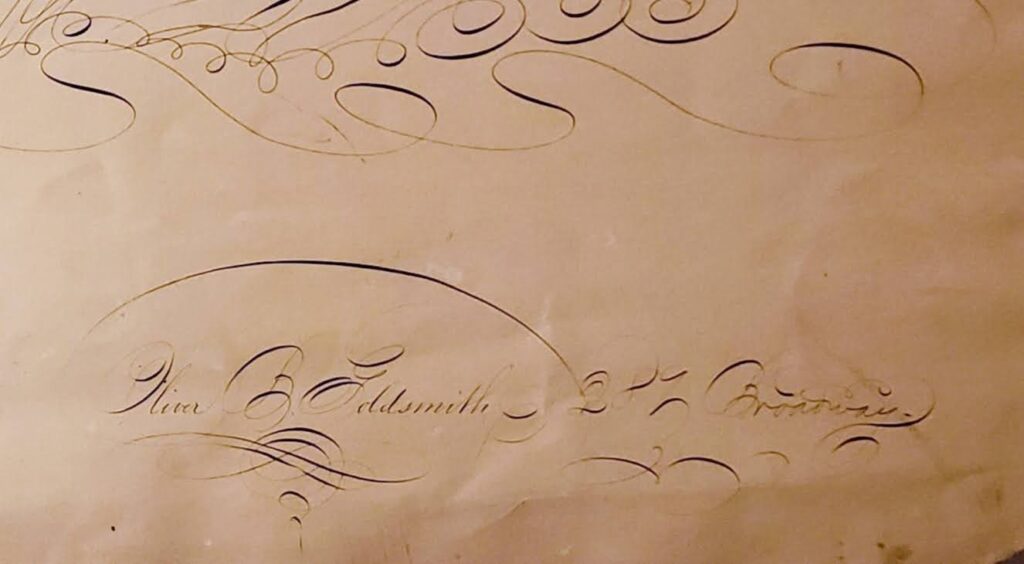

Below the drawing Goldsmith wrote the title of the piece, the person intended to receive it, and his own name and address in elegant penmanship with flourishes. The title, “Marsh Hawk,” appears in the center. Towards the left corner is an inscription that reads, “Presented to Victor G. Audubon, Esq. by,” followed by the words, “Oliver B. Goldsmith 289 Broadway,” towards the right corner.

“Marsh Hawk”

“Presented to Victor G. Audubon, Esq. by”

“Oliver B. Goldsmith 289 Broadway”

What does this information tell us? Let’s take a look at the recipient of the drawing. “Victor G. Audubon” was Victor Gifford Audubon (1809-1860), John James Audubon’s oldest son and business manager. We know that Victor Gifford received and kept the drawing since it was passed down through his family to Leonard Sanford Tyler (1881-1928), his great-grandson. In 1938, Tyler’s wife, Alice Dickson Jaynes Tyler (1883–1951), loaned this drawing along with many other Audubon artifacts to the new museum at Audubon State Park in Henderson, Kentucky. The Audubon Museum later acquired the piece from the Tyler family for its permanent collection.

There is no date written on the drawing and no supporting documentation to tell us when Victor Gifford received it. We can only estimate a span of years for the creation of the piece: sometime between 1838 and 1860. Goldsmith most likely would not have produced the Marsh Hawk before 1838. According to his obituary, he did not start studying penmanship until 1837. A year later in 1838, he opened a school to teach this skill in Brooklyn, New York. The address written with Goldsmith’s name on the drawing (289 Broadway) matches his address listed in the 1850 New York Mercantile Union Business Directory. There he is listed as “Goldsmith, Oliver B. 289 Broadway,” under the category of Penmanship. This confirms that the address on the drawing matches a known address for Goldsmith’s school during our estimated span of years for the drawing’s creation. Since Victor Gifford died in August 1860, we calculate that year as the last possible date of production. Based on this approximation, we think Goldsmith’s drawing is between 160 to 182 years old. It remains in fair condition for its age, flat and mostly uncreased with some foxing, darkening of the paper, and small tears along the edges.

Now that we know the identities of the artist and recipient of the Marsh Hawk, an estimated range of dates for its creation, its title, and its connection with a penmanship school, what questions can we ask about its context? For instance: Why did Goldsmith dedicate this drawing to Victor Gifford Audubon? Why create the piece in the first place? Was there a connection to Victor Gifford’s father, John James Audubon? What purpose did it serve to include the school’s address on the drawing? Taking a closer look at the Marsh Hawk’s imagery and considering Goldsmith’s position as a penmanship instructor may help us come up with some theories.

An Homage to John James Audubon

https://www.audubon.org/birds-of-america/marsh-hawk

The title of Goldsmith’s drawing, Marsh Hawk, along with the dedication to Victor Gifford Audubon point to his inspiration for the piece. Above is John James Audubon’s illustration of the Marsh Hawk from the Double Elephant Folio of The Birds of America (plate 356). Take a moment to compare this print to the calligraphic drawing. What similarities do you see between the two works? Can you spot the differences?

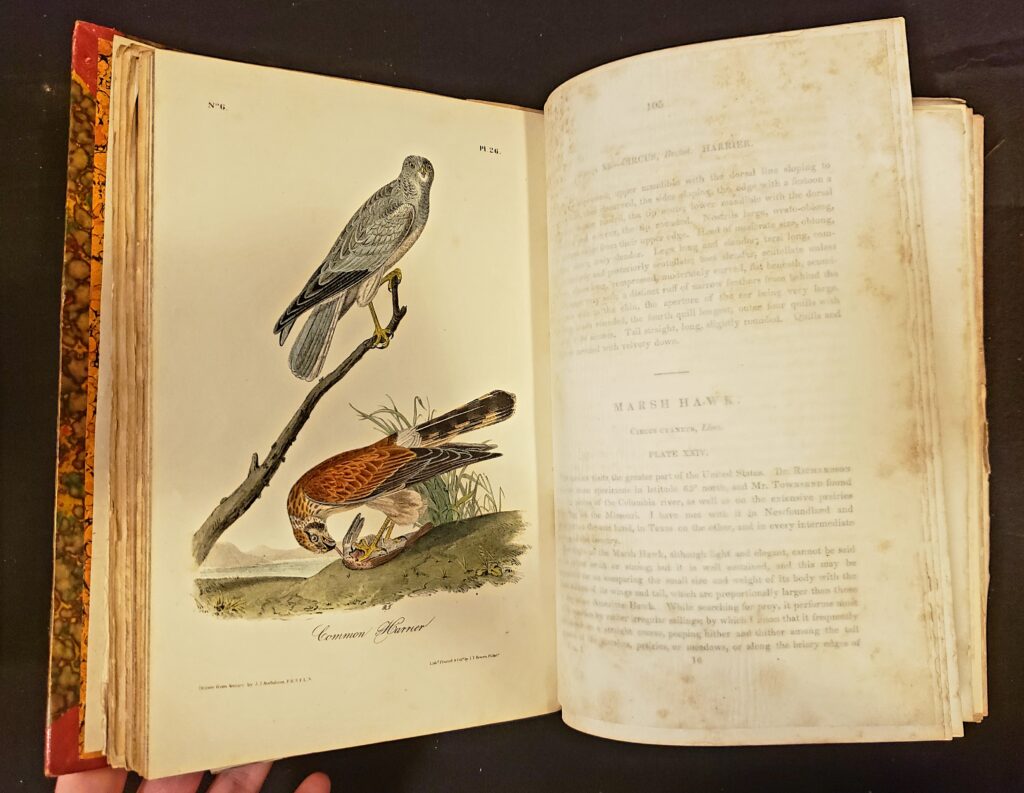

In Audubon’s print, there are three birds. At the top is a young bird perched on a branch, turned slightly to face the right. An adult bird in the center sits on another branch with its face turned towards the viewer. At the bottom another young bird eats its prey on the ground near a tall plant, some of the leaves bent by the bird’s weight. In the background are distant mountains and a body of water. Goldsmith retained the two birds perched on the branches, but deleted the third bird on the ground. He also left out the background of mountains and water, choosing to add more tall grass and make slight changes to the branches. The two hawks are shown in the same positions as the Audubon print – the young hawk turned slightly to face the right and the older hawk turned to look at the viewer.

Goldsmith must have closely studied Audubon’s Marsh Hawk to creatively translate the other artist’s illustration into a calligraphic drawing of his own. What’s intriguing is that he seems to have taken the imagery from the double-elephant-sized print by Robert Havell, Jr. rather than the smaller print made by J.T. Bowen in the later Royal Octavo editions of The Birds of America. As you can see below on the left, the Havell print includes the young bird resting on the top branch, facing to the side. This bird and its branch disappear in the Bowen print.

Right: Bowen print of the Marsh Hawk in volume 4 of John James Audubon’s Ornithological Biography, 1838. Plates from a later Royal Octavo edition have been bound in this book. John James Audubon Museum Collection, JJA.1938.1517.

Another possibility is that Goldsmith may have viewed Audubon’s original watercolor of the Marsh Hawk that served as the model for the Havell print. Below is a reproduction of Audubon’s painting of the Marsh Hawk, which is now in the collection of the New York Historical Society. You can see that the young bird on the top branch is present here as well.

With the inclusion of the top bird in Goldsmith’s illustration, we could assume that he saw either a Havell print of the Marsh Hawk or the original painting by Audubon, and made his drawing based on the imagery in those works. Though much of the composition is the same (the positioning of the two birds, their expressions, the placement of the branches and grasses, for example), there are enough differences that you can still view Goldsmith’s drawing as an individual unique work of art. He translates Audubon’s depiction of the Marsh Hawk into calligraphic art, paying respect to the other artist’s depiction of the birds while using his technical skills as a master penman to create a work with originality. This concept in art is called homage.

Goldsmith’s Motives

Was this drawing simply a gift from Goldsmith to John James Audubon’s son with no other motives behind it? Without additional evidence, we can only speculate about his reasons for creating the piece. It is clear that Goldsmith was paying homage to the illustration of the Marsh Hawk in The Birds of America, a publication that had made Audubon internationally famous. As a businessman who needed to attract students to his penmanship school, perhaps Goldsmith viewed the Marsh Hawk as a potential advertising opportunity. Self-promotion through demonstration of skill was not unusual in the 19th century for a professional penman like Goldsmith, as suggested by American calligrapher Charles P. Zaner in his book Zaner’s Gems of Flourishing (1888):

“If you are a teacher of penmanship, much of your success depends, in many instances, upon your ability to flourish, as there is no one thing so easily and quickly made that will attract as much attention as a skillfully executed flourish.”

Charles P. Zaner, Zaner’s Gems of Flourishing (1888)

Goldsmith and other penmen used calligraphic art to show off their technical skills in creating decorative letters and images of plants and animals (including birds). In the case of Goldsmith’s Marsh Hawk, he was not only drawing birds and plants using offhand flourishing, but translating one of John James Audubon’s celebrated bird illustrations into calligraphy. Maybe the production of the Marsh Hawk was actually a publicity stunt. With this drawing, Goldsmith may have been riding on Audubon’s coattails with the aim of attracting attention to himself and the skills he could teach students in his penmanship school, the address of which is conveniently listed at the bottom of the page.

Why did Goldsmith dedicate the Marsh Hawk to Victor Gifford and not John James Audubon himself? Perhaps this drawing came after Audubon’s death in 1851 and Goldsmith created it as an homage. Perhaps he was a friend of Victor Gifford and simply wanted to offer it as a gift. Or perhaps Goldsmith was aware that Victor Gifford was his father’s business manager and he wanted to offer his services for creating the title page of a future Audubon publication. Without other evidence, we will probably never know why the drawing was given to Victor Gifford or Goldsmith’s motives for producing it.

In the Museum

Victor Gifford Audubon and his descendants through the Tyler family kept and preserved Goldsmith’s lovely calligraphic drawing for close to a century before it came to the Audubon Museum. Obviously the piece had value to them — most likely because it pays homage to John James Audubon’s work in The Birds of America. Alice Dickson Jaynes Tyler loaned the Marsh Hawk to our museum starting in 1938 as part of a large collection of “Auduboniana” that had been saved by the family over the years. The drawing and many other items from the Tyler family were later purchased for the museum’s permanent collection. So what value does the Marsh Hawk have for us today and why do we continue to preserve it for future generations?

Museums do not collect things just for the sake of collecting. The value of an object lies in the stories that it enables museums to tell and the connections it can help make to new ideas and new contexts. Goldsmith’s Marsh Hawk offers us both possibilities. For instance, we could use the drawing to talk about parallels between Goldsmith and John James Audubon as men who lost their businesses in financial crises and had to reinvent themselves using their artistic talents. We could also discuss the idea of artistic homage and relate Goldsmith’s adaptation of Audubon’s Marsh Hawk in The Birds of America to contemporary examples that reference Audubon’s work, such as Tom Sanford’s California Condor in the 2017 101/EXHIBIT show, “Explorations of Audubon: The Paintings of Larry Rivers and Others.” What infuses Goldsmith’s Marsh Hawk with value are the stories we could tell from what we know of its history, and its potential use in making connections to the world outside our museum. We preserve the drawing so that curators and others in the future can continue to tell its stories and discover relevance for their world.

This post was written by Heidi Taylor-Caudill, museum curator at John James Audubon State Park. Questions? Contact Heidi at heidi.taylorcaudill@ky.gov.

SOURCES:

- Anderson, Donald M. “Calligraphy: Writing Manuals and Copybooks (16th to 18th Century).” Brittanica. Accessed October 12, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/art/calligraphy/Writing-manuals-and-copybooks-16th-to-18th-century.

- Appletons’ Annual Cyclopedia and Register of Important Events: Embracing Political, Military, and Ecclesiastical Affairs; Public Documents; Biography, Statistics, Commerce, Finance, Literature, Science, Agriculture, and Mechanical Industry, Volume 28. Appleton, 1889. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=WgwbAQAAMAAJ&pg=PP7#v=onepage&q&f=false

- “Birds of America: Explorations of Audubon: The Paintings of Larry Rivers and Others.” 101/EXHIBIT. Accessed October 12, 2020. http://www.101exhibit.com/exhibitions/birds-of-america.

- Callaghan, Meaghan Lee. “A New Exhibit Puts a Modern Spin on the Renowned ‘Birds of America’ Paintings.” National Audubon Society website. Audubon Magazine, March 30, 2017. https://www.audubon.org/news/a-new-exhibit-puts-modern-spin-renowned-birds-america-paintings.

- Goldsmith, Oliver B. Goldsmith’s Gems of Penmanship, Containing Various Examples of the Caligraphic Art, Embracing the Author’s System of Mercantile Penmanship, in Ten Lessons, of One Hour Each, with Ample Instructions. New York: Oliver B. Goldsmith, 1845.

- “Plate 356, Marsh Hawk.” National Audubon Society. Accessed October 12, 2020. https://www.audubon.org/birds-of-america/marsh-hawk.

- “Obituary, Oliver B. Goldsmith.” Times Union (Brooklyn, NY), April 30, 1888: https://www.newspapers.com/clip/33560817/oliver-b-goldsmith-penmanship/.

- The New York Mercantile Union Business Directory. New York: S. French, L.C. & H.L. Pratt, 1850. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=XtsCAAAAYAAJ&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false