Museum Monday videos feature stories from the museum collection and the history of John James Audubon State Park.

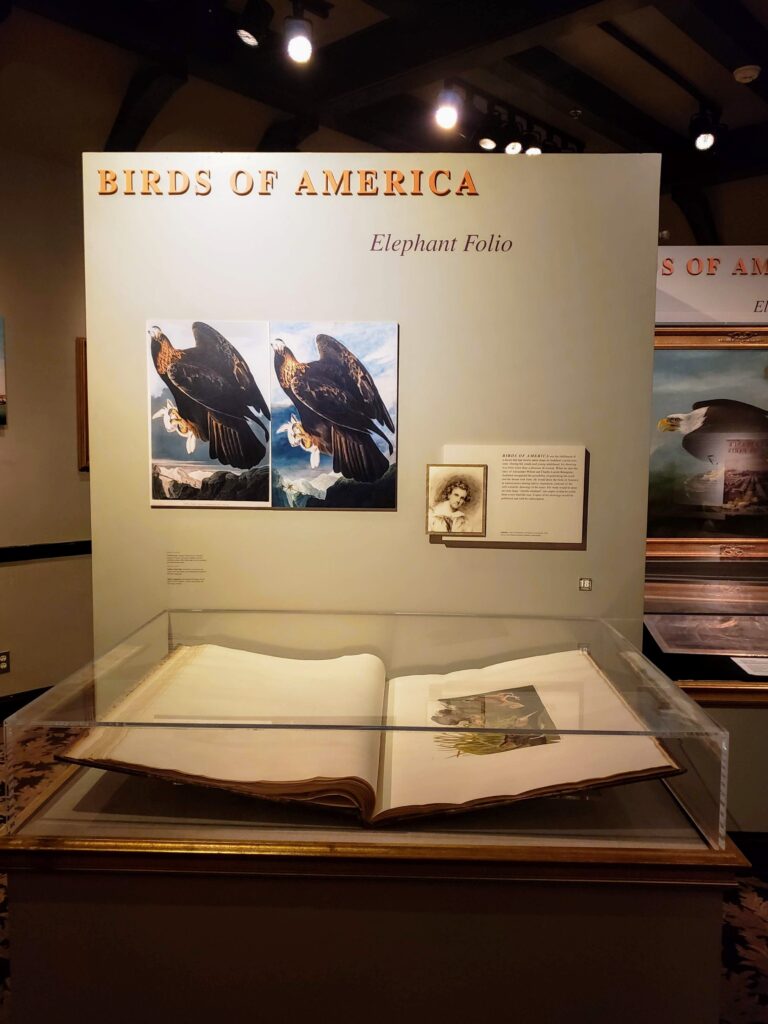

Join our curator, Heidi Taylor-Caudill, for a new Museum Monday video about the printing of the original double-elephant edition of The Birds of America. Hear the story of John James Audubon and his search for a publisher for the project, learn about the process of engraving, printing, and coloring prints for the book, and take a closer look at details of three owl prints produced by Audubon’s engraver, Robert Havell, Jr.

Questions? Contact Heidi at 502-782-9716 or heidi.taylorcaudill@ky.gov.

Transcript of Video:

Welcome to Museum Monday at John James Audubon State Park in Henderson, Kentucky. My name is Heidi Taylor-Caudill and I am the museum curator here at the park.

Barred Owl

Great Horned Owl

Snowy Owl

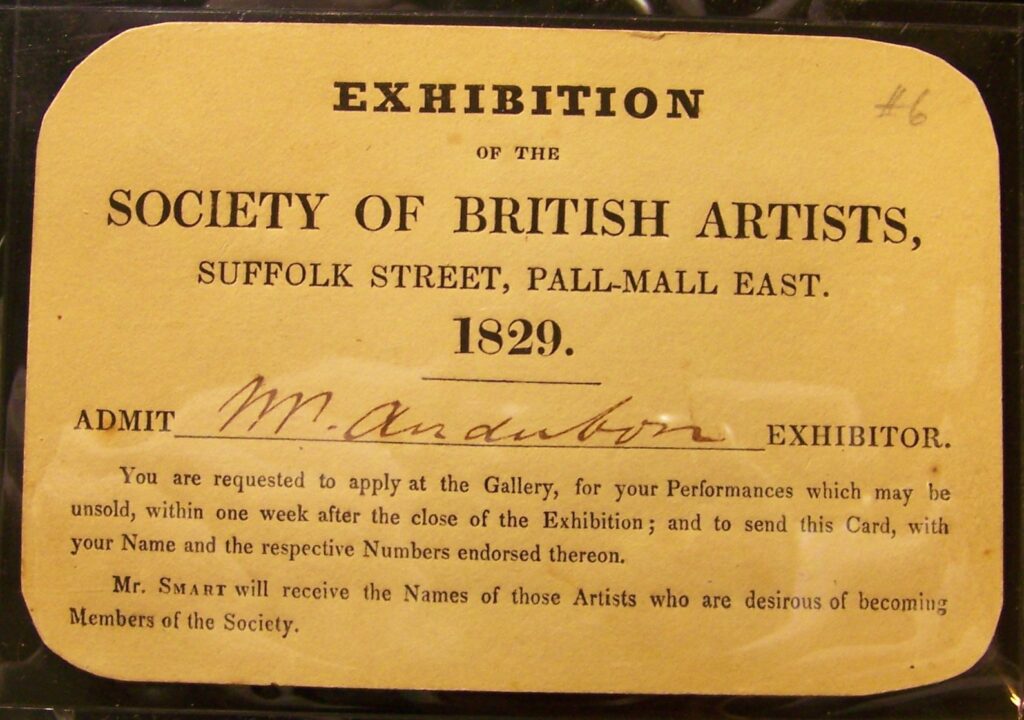

For this week’s Museum Monday video, we’re going to take a closer look at three of John James Audubon’s owl prints for The Birds of America. These prints – the Snowy Owl, the Barred Owl, and the Great Horned Owl – were produced by London engraver Robert Havell, Jr. between 1828 and 1829. I will share a bit of information with you about John James Audubon and the idea for The Birds of America, describe the process for making the prints, and then look at details from the three owl prints.

John James Audubon arrived in England in July 1826 with an ambitious idea. He wanted to find an engraver who could publish his bird paintings as life-sized prints on double-elephant folio paper, which is approximately 26 1/2 x 39 inches. None of the American engravers he had approached wanted anything to do with the project. One of their major objections was the size of his drawings. Audubon drew his birds at their natural dimensions.

John James Audubon State Park Museum Collection, 1938.1500

For larger birds like eagles and turkeys, he used the largest available paper size – the double-elephant paper – to fit them on the page. He resisted the idea of scaling down the birds from their true size. In response, the American engravers told him that publishing such large color images would be impossible. First, producing the prints would be too costly and second, even if it could be done, who would want to buy such a large and expensive book? Some of Audubon’s supporters in America who admired his drawings and sympathized with his idea, suggested that he may be able to find a publisher in Europe who could handle such a challenging project.

L.S. Tyler Collection, 1938.415

John James Audubon State Park Museum

Audubon spent his first four months in England exhibiting his bird paintings in various galleries. After seeing so many people admire and praise his work, he decided to continue with his original idea to publish the drawings at life size. He would sell his work by subscription, the proceeds of which would enable him to fund the costs of engraving, printing, and hand-coloring the prints. Now Audubon just needed to find a publisher willing to take on the project.

It was in Edinburgh where Audubon found his first engraver for The Birds of America, William Lizars. Unfortunately, Lizars was only able to engrave and print the first ten prints when his team of printers and colorists went on strike. Audubon subsequently ended his contract with Lizars and turned to the London firm of Robert Havell and Son. By the end of 1827, enough prints had been completed by the Havells that Audubon could publish an announcement about The Birds of America and start selling subscriptions.

The work would take thirteen years to complete. Today, The Birds of America stands as one of the most expensive and ambitious publishing projects in history.

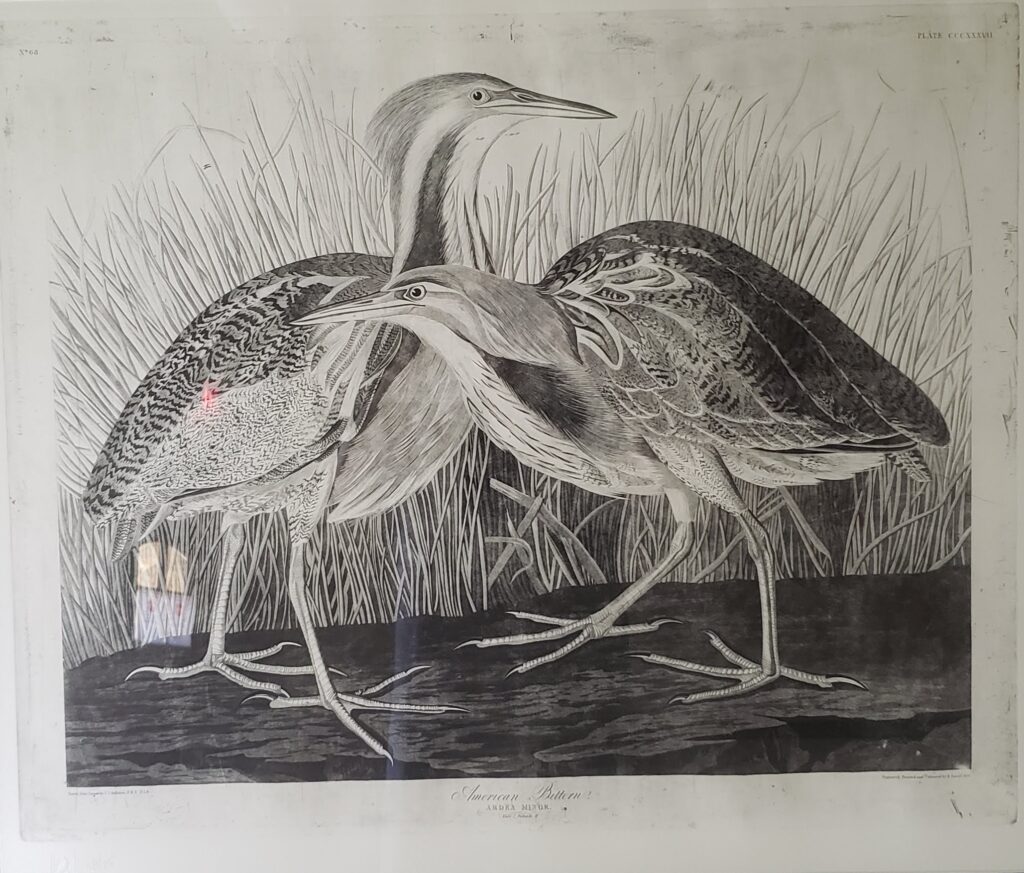

To help us better appreciate the level of detail and artistic skill shown in the Havell prints, I need to tell you about how these prints were made. It was a four-step process:

First, the printer carefully traced the outlines of Audubon’s finished painting onto thin paper.

Second, the traced image was transferred to the surface of a copper plate through the intaglio printing techniques of engraving, etching, and aquatint. Basically, the image would be cut into the copper surface of the plate either using a cutting tool held in the hand – which is called engraving – or through corrosion by acid – which is known as etching. Aquatint is a variation of etching that produces tonal areas instead of fine lines.

#337 American Bittern, 1836

Friends of Audubon Collection, 2007.4

John James Audubon State Park Museum

Third, the design on the copper plate would be printed in black ink on white paper using a press. The process for doing this involved filling the incised line or sunken area with a greasy black ink and carefully cleaning the rest of the surface so that the ink remained only in the cut design. The inked plate was then pressed against the paper using a rolling press that applied very high pressure. The image that came out was very fine and sharp.

#337 American Bittern, 2013

John James Audubon State Park Museum

Fourth, a team of watercolorists carefully colored in the black-and-white image by hand. Audubon and his son Victor watched the coloring process very closely and did not hesitate to return prints that were not done to their standards.

Image: National Audubon Society

https://www.audubon.org/birds-of-america/american-bittern

The finished Havell prints are absolutely beautiful. Audubon and Robert Havell, Jr., who completed most of the prints in The Birds of America, tried to depict the birds as accurately as possible. Looking closely, you can see the extreme level of detail that Audubon captured in his paintings and that Havell meticulously reproduced using very fine, sharp printing.

Robert Havell, Jr. (1793-1878), engraver

Barred Owl, 1828

Henderson County Historical Society Collection, 1938.1505

John James Audubon State Park Museum

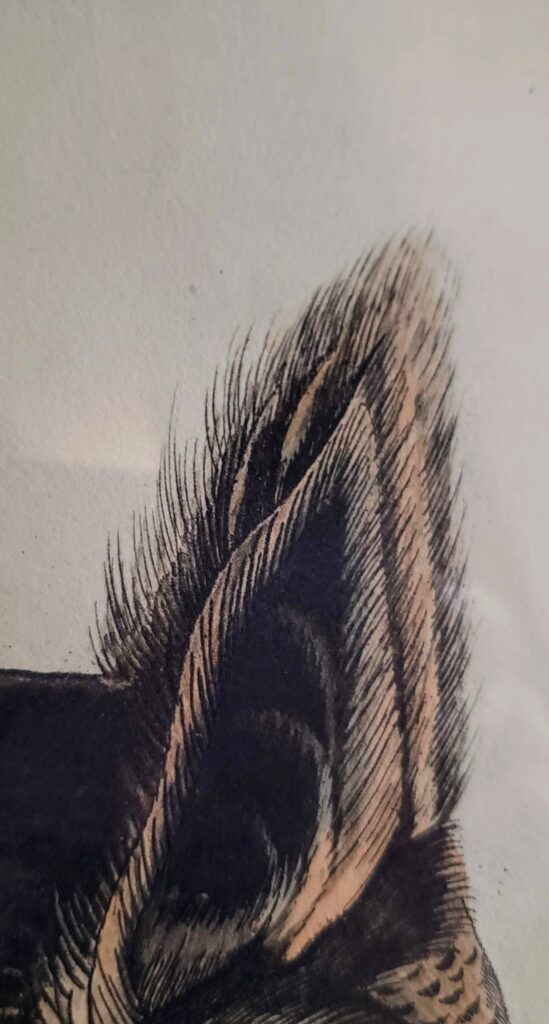

Here is Audubon’s illustration of the Barred Owl, plate #46 in The Birds of America. This print depicts a brown and white owl that has just landed on a tree branch, startling a squirrel. Let’s take a few moments to examine some of the details of the print.

Do you see how the texture and form of the feathers of the owl’s outstretched wing are captured through the use of fine lines and shading? The rachis of the feather – which is the long, slender central part – is represented using evenly-spaced, diagonal lines that slant to the right and a long, thin black line on the left side, to show a shadow. Juxtaposed with these are the evenly-spaced, horizontal lines of the barbs, which grow from the rachis. Carefully placed highlights of white paint on the right side of the rachis also help define the shape of the feathers.

I also want to point out this small detail from one of the feathers of the owl’s left wing. You can see how the lines of the barbs are so finely captured that the edge of the feather is implied, rather than drawn. If you look at a feather in real life, you’ll also notice this implied line along the vane. Our brains fill in the line from the void.

Robert Havell, Jr. (1793-1878), engraver

Great Horned Owl, 1829

Henderson County Historical Society Collection, 1938.1497

John James Audubon State Park Museum

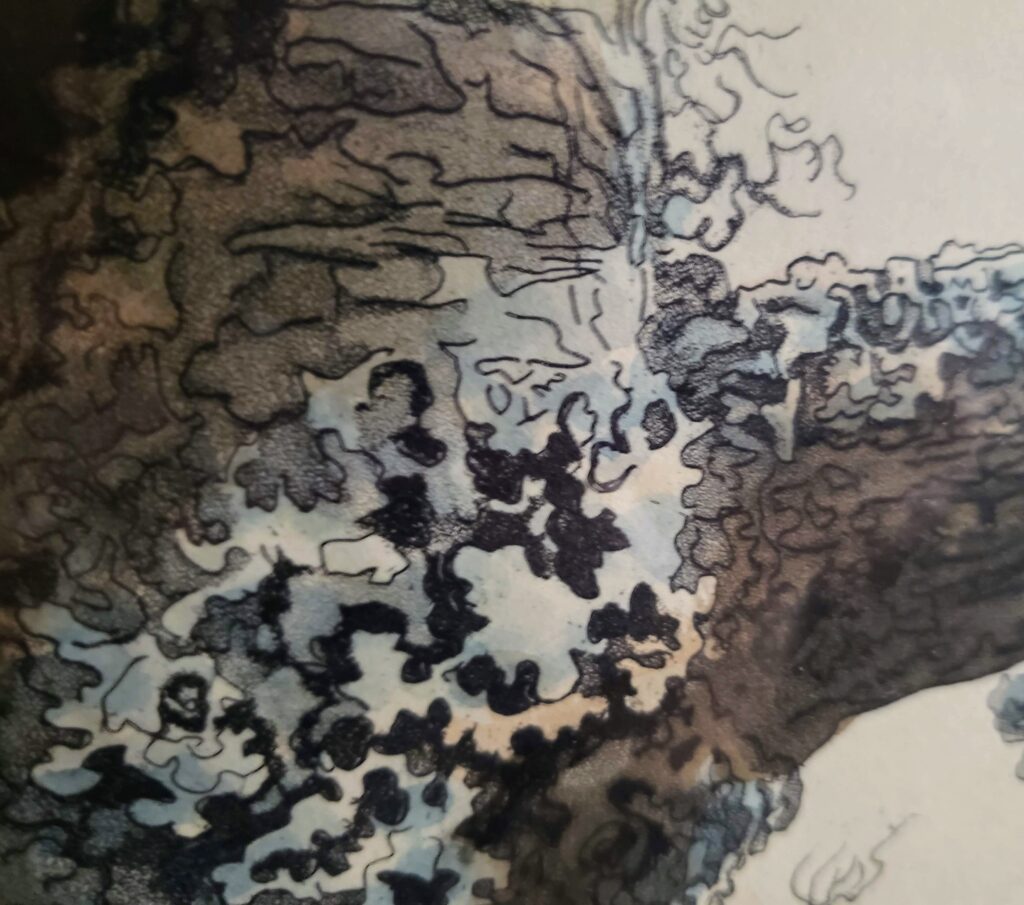

This print of the Great Horned Owl, plate #61 in The Birds of America, is very interesting for all its different patterns and textures. Looking closely at the patterns in the owls’ feathers, you’ll notice a variety of irregular shapes made of closely spaced black lines. Many of these look like the lines on a Richter scale to measure earthquakes.

Some of these shapes are overlaid with regular lines that represent the barbs of the feathers. The subtle color shading of the feathers is also gorgeous.

Compare the patterns of the owl feathers with the lichen growing on the tree branch. How do you think these lines and shapes depict a different texture than the ones that make up the feathers?

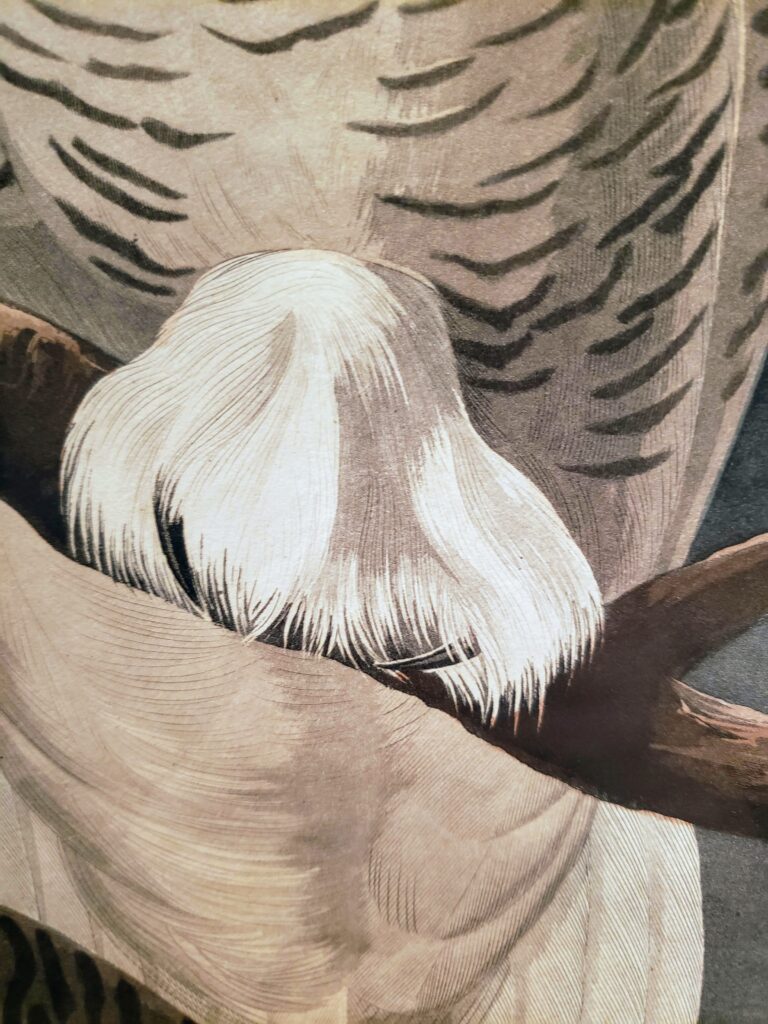

And finally, let’s take a moment to study this beautiful print of the Snowy Owl, plate #121 in The Birds of America. Since the owls are mostly white in color, the engraver used very fine, light gray lines and subtle washes of grays and browns to depict the feathers.

Robert Havell, Jr. (1793-1878), engraver

Snowy Owl, 1829

John James Audubon State Park Museum Collection, 1938.1493

From a distance, you wouldn’t see these details. It’s only up close that you can really see how intricate the composition is and appreciate the artistry that went into creating this piece.

We are very fortunate to have these original Havell prints and others to share with visitors to John James Audubon State Park. In the future, when we reopen the museum, consider coming by for a visit to take a closer look at the prints and learn more about Audubon’s journey to producing The Birds of America.

As always, stay safe and be well.

End of Transcript